Analyzing the Telephone Call

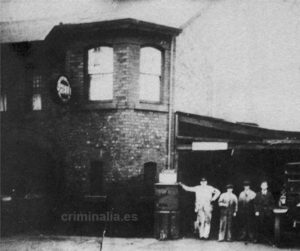

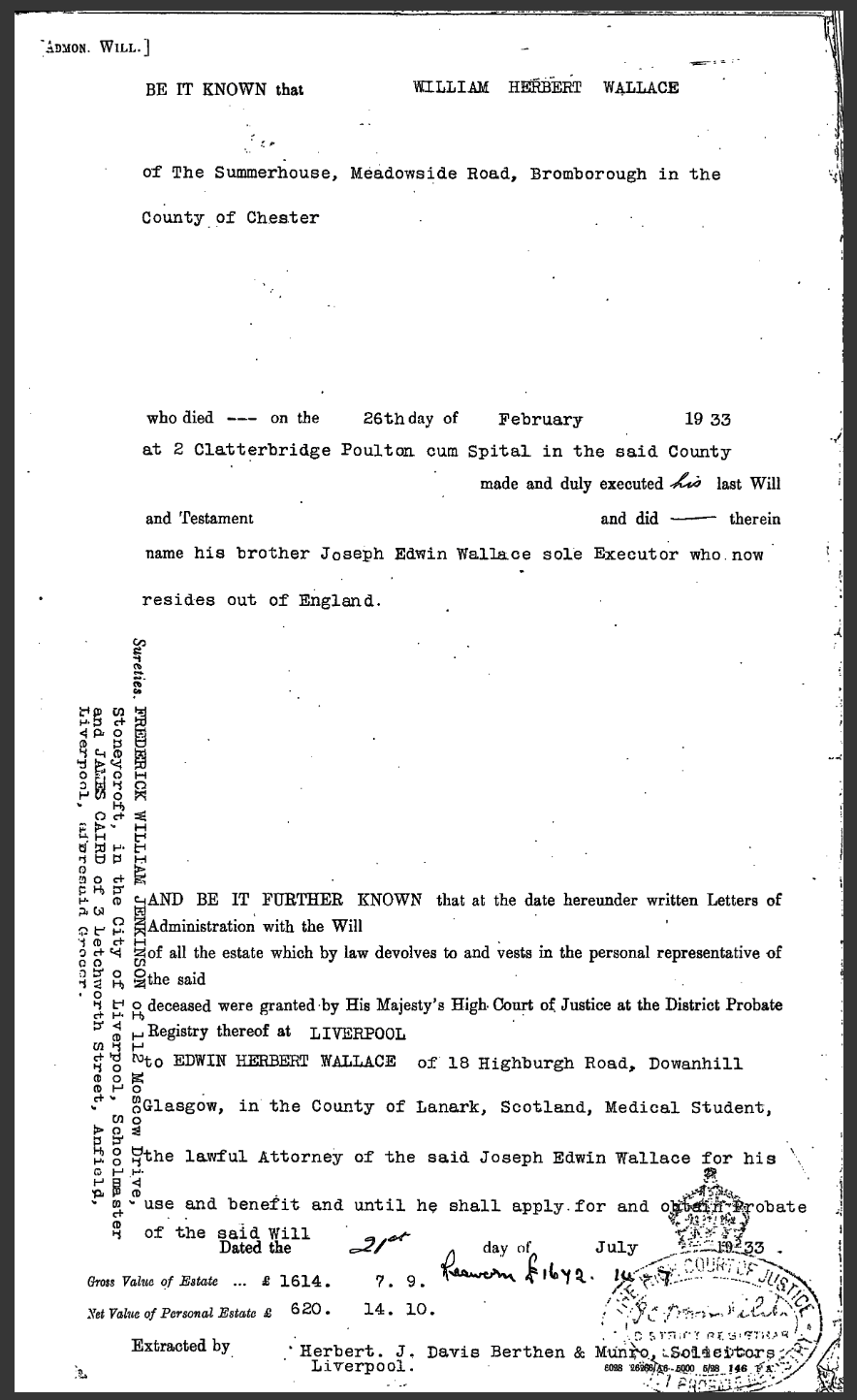

In a case revolving around the placement of a telephone call, it is of course natural that we start where it all began, at telephone box “Anfield 1627”. This was also one of the police’s first port of calls when they began their investigation, and the surprising findings helped them to solve the murder.

Phone Call Dialogue Transcript:

As gathered from various testimony and trial statements, the full call from exchange pickup to caller hangup should be something like this:

https://www.williamherbertwallace.com/case-files/qualtrough-call-dialogue/

—

Timing & Proximity:

A lot was made of the proximity of the telephone kiosk to Wallace’s home, and the fact that he could by the established times have placed the call and arrived at the chess club between 7.45 and 7.50 PM. These times are derived from various statements by chess club members including James Caird who turned up about 7.35 and said Wallace arrived around ten minutes later, Samuel Beattie who says that inquiring around he can state Wallace did not turn up before 7.45, and Wallace himself who first gave his arrival time to the club as around 7.50.

While the time that Wallace left his home dovetails with him being the caller, it matches a number of other possibilities which we will address in order:

A) That someone was waiting for him to leave his house to ascertain he was probably going to the chess club, then made the call.

This would entail somebody knowing that William goes to the chess club on Monday evenings, and knowing the approximate window of time in which he is likely to leave the house. Club members could turn up at a wide range of times: For example Samuel Beattie gets to the club at 6.00 PM, and is already engaged in a chess match with another person at 7.20 PM when the “Qualtrough” call comes in; James Caird turned up at 7.35 despite having no scheduled match; and Wallace himself does not arrive until 7.45 to 7.50.

The individual doing the stalking would have to wait on a street corner somewhere without a concrete idea of when Wallace might emerge from his house, unless the alleged stalker had also previously been watching the times he generally turned up to the club (a factor which is unknown: it was never brought up what time he usually arrives).

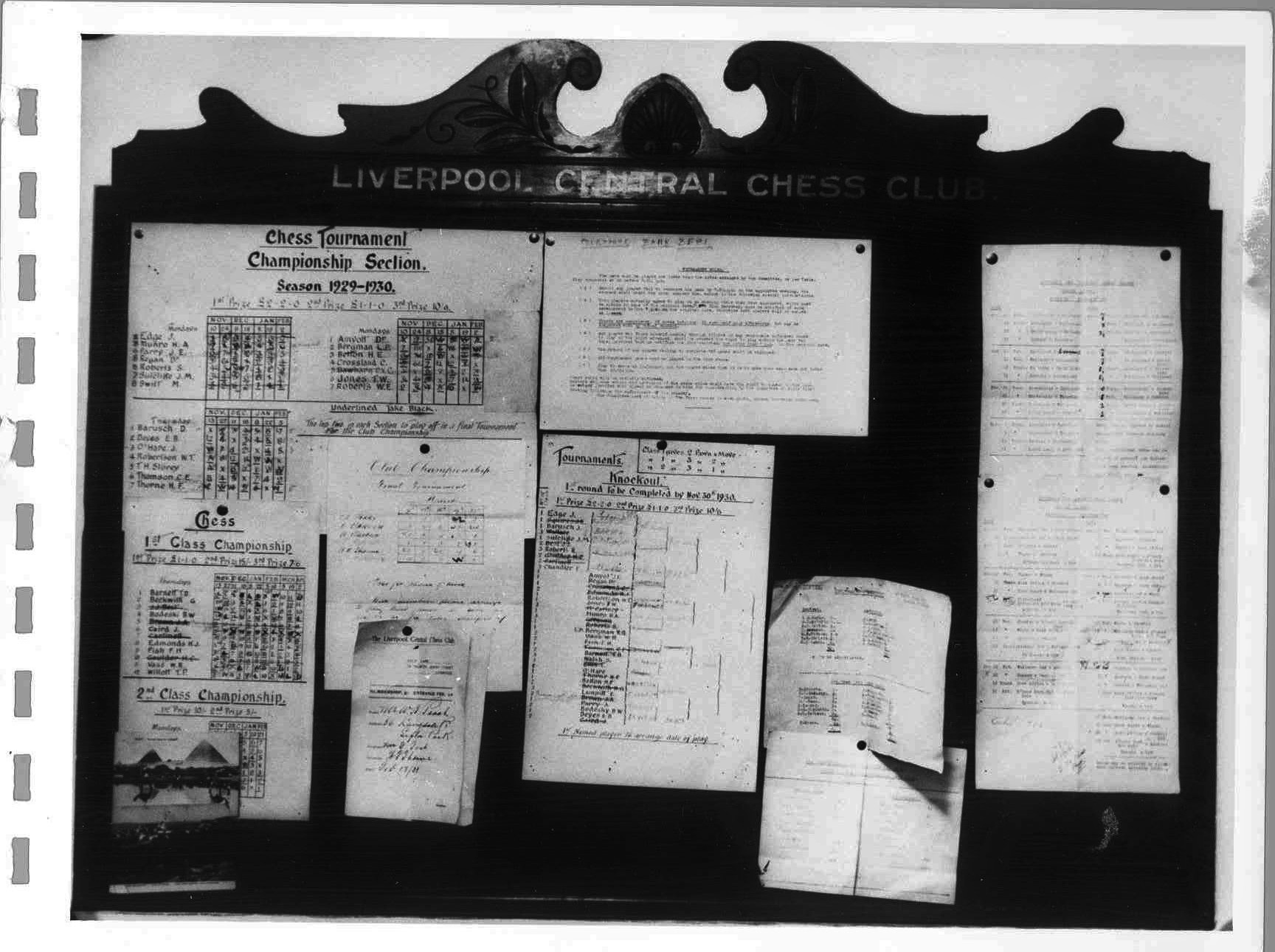

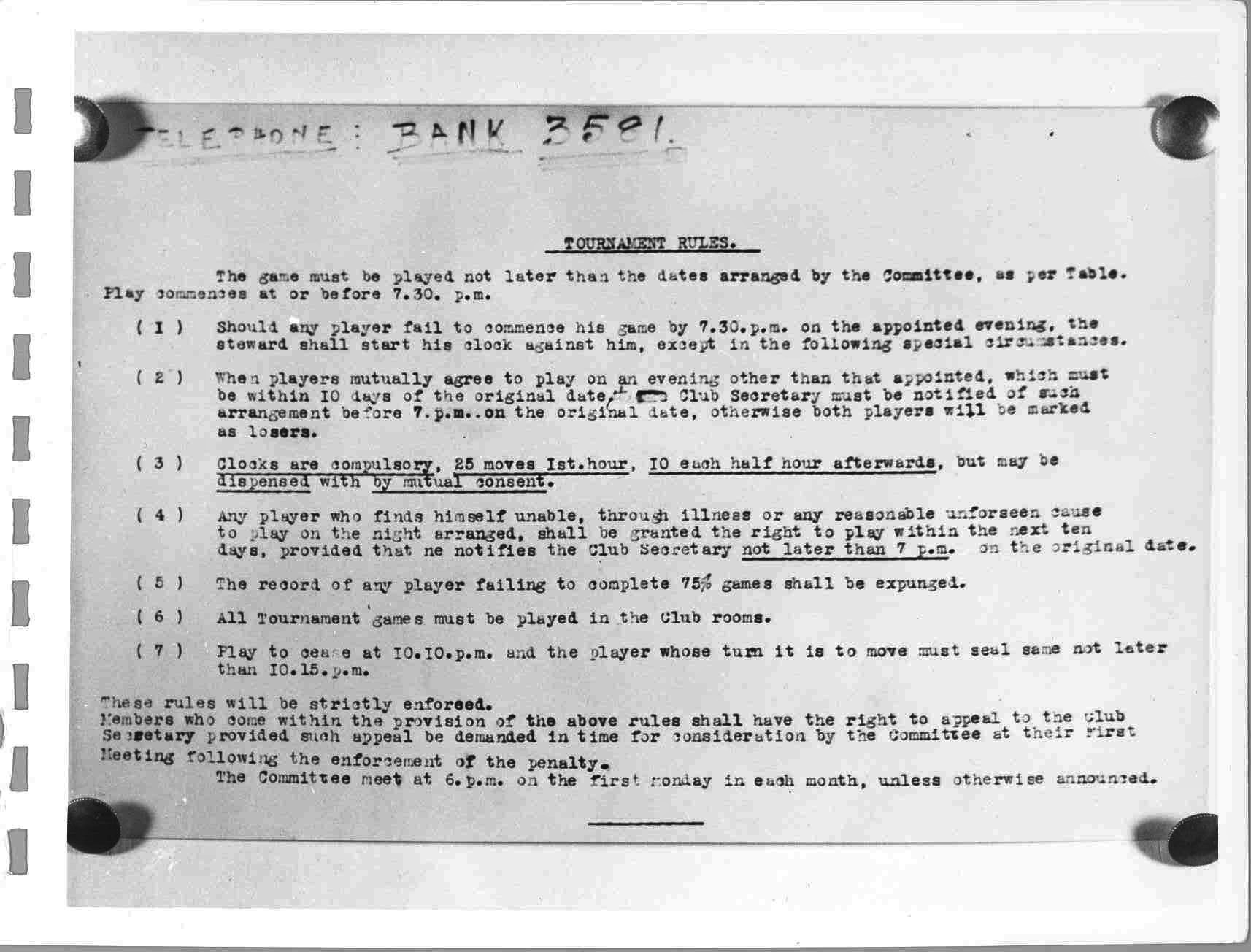

The individual could gain an idea of when Wallace might get to the club by checking the chess club noticeboard in the café. Tournament matches are scheduled to begin at a certain time and this time as well as the dates for upcoming matches are found upon that noticeboard. The noticeboard is only for the chess club, and anyone who is not a member of the chess club and who is not planning this crime, would not have any reason to look at anything posted upon it. Although Beattie claims the latest a person could turn up for a match without incurring a penalty is 7.45, the noticeboard states a “strict” start time of 7.30 instead, which is what someone studying this board could see. If this rule changed to 7.45 or if the rule was not strictly adhered to, it would be known to the members of the club, but probably not to outsiders.

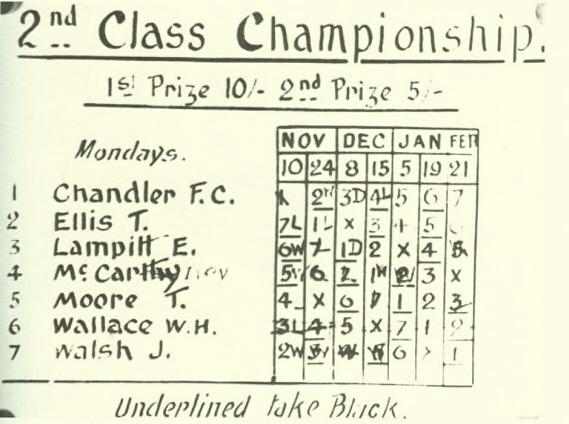

(Something like a leaflet showing the pyramids of Egypt is seen on the bottom left, and covers much of the chart in question. Of course, if this was there at the time of the crime Wallace’s name would not be visible to anyone studying the board).

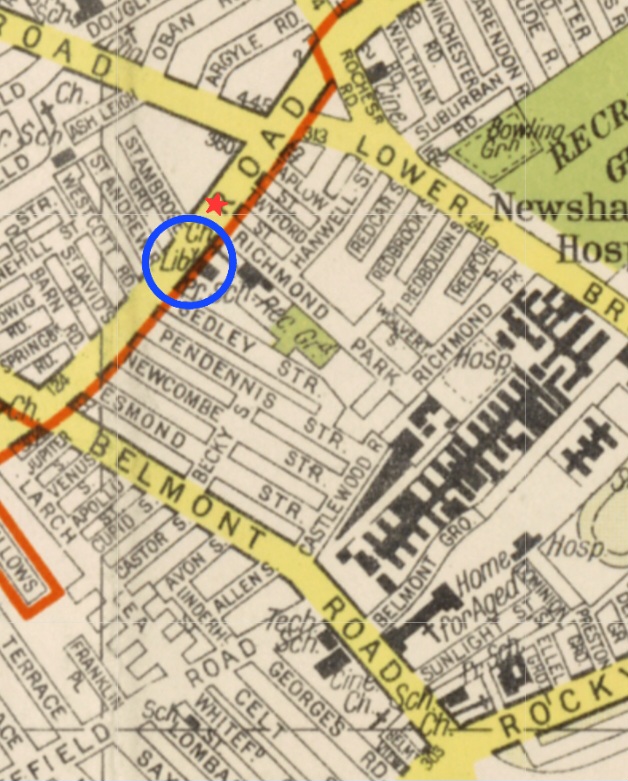

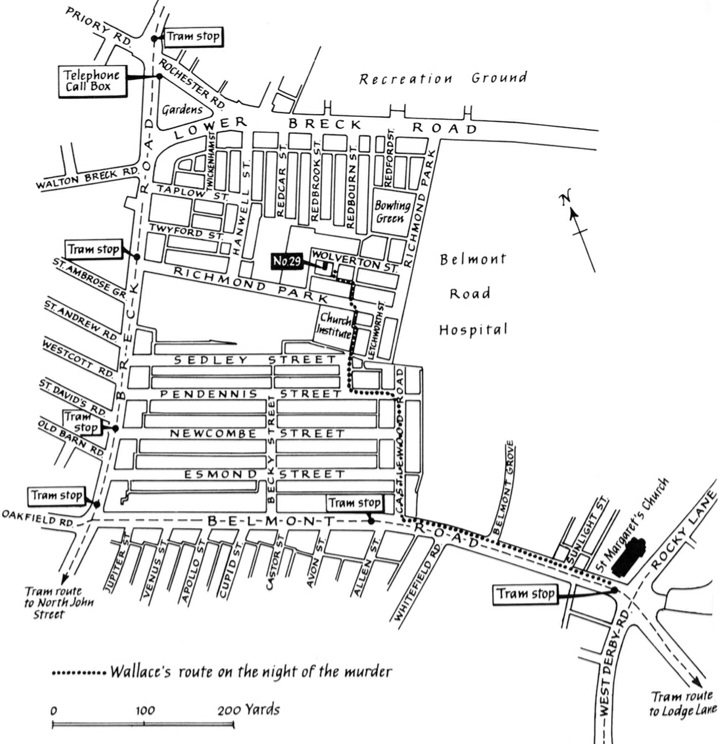

If a person had studied this noticeboard, had seen the match date and the match start time (listed as 7.30 PM), and staked out the Wallace house with the intention of ensuring he was going to his club that night, they might conclude that he was not going and call off the stakeout when he failed to emerge from his home until around 7.15. By leaving his home at 7.15 or even a bit before – even as early as 7.10 – it would be impossible by any tram stop to turn up to the chess club on time for the 7.30 match time listed on the noticeboard. The closest tram stop is a 3 minute walk at an average pace (Wallace did not use this one, he alleges to have walked past two tram stops to board at Belmont Road), and the journey is at least 18 minutes. This does not even include the wait time for the tram which averages 4.5 minutes.

Therefore to arrive at the chess club on time for a match a person would want to leave 29 Wolverton Street by 7.00 PM, which allows for an 18 minute tram journey time (includes the short walk to the café) + 4 minute wait for a tram + 3 minute walk to the nearest tram stop at Richmond Park (243 yards), arriving at the chess club at 7.25. Since trams could require a wait of up to 8 or 9 minutes, if a person just missed the tram at Richmond Park and waited the full 9 minutes they should theoretically turn up dead on 7.30 for the match.

As proof of this, we can see from the time Wallace arrived at the chess club that he is substantially late compared to the listed match start time, turning up 15 to 20 minutes after 7.30. Wallace has stated that he may even have left the house as late as 7.20 PM for the club which would make his emergence from his home even later than it already was:

“I left for the Chess Club (City Cafe, North John Street) about 7.15 or 7.20”

If the stalker had not discovered the match times by the noticeboard they would not have reason to know when match games are due to begin play. If they instead derived the time by simply going to the café and observing when games of chess start, they would see members in matches at earlier times than listed on the board: As seen, Beattie is already in a game with someone at 7.20 on the night the call was made.

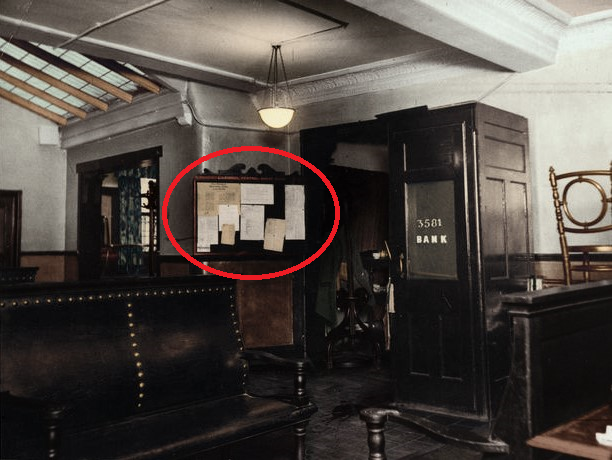

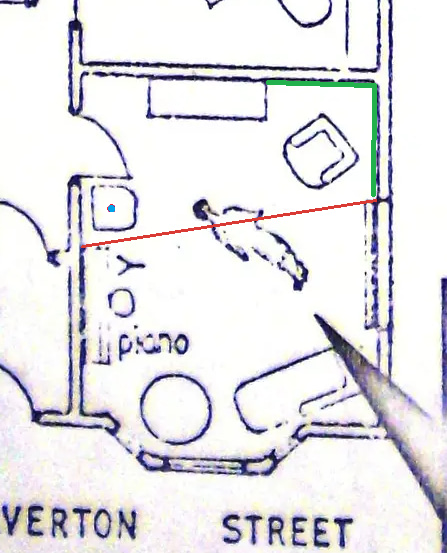

The café had four separate rooms. The chess club noticeboard was beside the café’s telephone box from which Gladys Harley and Beattie spoke to “Qualtrough”.

184. How big is this Cafe, is it a big place? Yes.

185. How many rooms are there? Four.

186. All on the ground floor? Yes.

187. And there are a lot of tables? Yes.

188. Do you have many customers? Yes.

189. Have you any idea how many people use your restaurant every day. Would it be a hundred? Yes, it would be about that.

190. A hundred? Yes.

191. I do not want to ask you a lot about the Chess Club because I will get it from somebody else, but there is a Chess Club which uses some of the tables in your room on certain days? Yes.

192. Have they got a notice posted up near the doorway of your restaurant? No.

193. You may not have noticed them, but there are some notices up, are not there? Yes, on the side.

194. Whereabouts are they? By the telephone box.

It is not clear where the entrance to the café is in relation to the noticeboard, which of the four rooms the entrance led into, or which of the four rooms were used by other clubs which met at the café such as the Merseyside Amateur Dramatics Society.

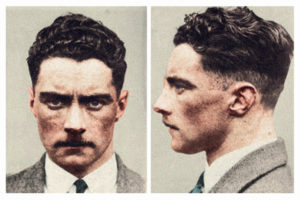

Gordon Parry – the Iago of Anfield:In a scenario where Wallace has no involvement in his wife’s murder, Gordon Parry is generally posited as the main alternative suspect behind the call. He is aware that William is a member of the chess club at the café, knows that William is an insurance agent (Beattie who knew Wallace for years did not), knows the location of the Prudential cash box in Wallace’s house, and has a criminal record. Other factors which make him a good suspect are his arrival time at Lily Lloyd’s house, which makes it possible for him to have made the “Qualtrough” call from the telephone box near Priory Road beforehand. Critically, he provided a false account of his whereabouts for the day the telephone call was made.

He would know the café where the meetings took place as he had been there before attending his own club (an amateur dramatics society). However, Gordon has never been shown to have been at the café on Mondays to know there were chess meetings on Monday evenings at all. As he states:

I am a member of the Mersey Amateur Dramatic Society and previous to the production of “John Glaydes Honour” on November 17th 1930, at Crane Hall, we were rehearsing at the City Cafe every Tuesday and Thursday. It was during these rehearsals that I saw Mr. Wallace at the City Cafe on about three occasions. I did not know previously that he was a member of the Chess Club there.

Wallace also makes a statement about seeing Gordon at the café, and verifies that he believes it had been a Thursday when this sighting occurred.

Gordon’s drama society met at the café twice a week on Tuesdays and Thursdays for a period of time ending on the 17th of November (while rehearsing for a play), a touch over two months before the crime. He had seen Wallace there during these rehearsals on three occasions. Since the dramatic society and chess club both met on Thursdays, but the chess club did not meet on Tuesdays, we can determine that all three of these sightings took place on Thursday. Therefore, we can only be sure that Gordon knows the chess club meets once a week on Thursday (he would see them meet every single Thursday while he attended rehearsals), and that William is a member of this club. Without Gordon doing any further digging such as studying the match chart or speculations as to other means by which he could gather this knowledge, he would not be aware that the club meets on Mondays too.

Two aspects which can be gained from the above:

1. Barring an unproven speculation such as Gordon gaining the information from a member of the club, or being a regular at the café and turning up on Mondays evenings during chess club times, he would have to study the match chart to see that the club meets on Mondays at all.

Additionally to this point, if he studied the noticeboard where the match dates were posted, the same noticeboard states clearly that 7.30 is when play is due to start. In the event of a “stakeout” where a person waits to see if William leaves his house for the club, they may believe he is not going and give up for the week, since Wallace was running 15 to 20 minutes for his game if you were judging by the noticeboard’s listed start time.

2. Since it has never been proven that Gordon went to the café again after the 17th of November, unless he was planning the crime since November when he is last known to have been there, he would not at that time have reason to pay attention to the chess club noticeboard. He would have no reason to notice/remember that the board even exists or the details of anything posted on it such as match dates and times.

He would also have had no reason to pay special attention to the time any members of the chess club are arriving. He would only be aware that during the window of time his dramatic society used to rehearse in the evenings, members of the chess club were also there, and that those club meetings happened on Thursdays.

3. The chess club tournament listings seem to have been posted up around Thursday the 6th of November. Wallace makes mention of the listings being up and seeing his tournament bracket in his diary entry for this date. Since Gordon’s drama club stopped meeting at the café by the 17th of November, this means there are only three evenings on which he might have spotted these listings by happenstance: the 6th, 11th, and 13th of November.

(4. It should also be mentioned that Gordon has a criminal record, and all known crimes he ever committed were opportunistic and spur of the moment, with absolutely no planning involved. He was often caught immediately. Crimes include vandalism, thieving from telephone boxes, hopping in and stealing cars, and a sexual assault charge against a girl he had taken out which he was acquitted of).

Since Wallace himself claims to have only ever seen Parry at the café once and on a Thursday (during a drama club rehearsal), and Wallace would show up to the club once or twice a week (according to Beattie) and had been a member of the chess club there for many years, it might suggest that – at least prior to the drama club rehearsals – Gordon was not in regular attendance of the café. If he was so often at the café we might expect more chance sightings than the three Parry gives/the one Wallace confirms.

If Gordon was “staking out” William, it is interesting that he or his car do not appear to have been spotted by William, considering the man is very familiar with him from their time working at the Prudential together.

The position that it was Gordon behind the scheme is weakened by his unproven knowledge of the chess club ever meeting on Monday, the lengthy time of two months since Gordon was last proven to have attended the café, and the M.O. being vastly different from Gordon’s string of impulsive spur-of-the-moment crimes before and after the murder. Because Gordon Parry is the only other known suspect who has access to all information necessary to carry out this crime, if he is not behind the scheme it is damaging to the possibility of Wallace’s innocence.

B) That someone knew roughly when Wallace usually attended his club, and simply placed a call a little before then (no stakeout).

There is nothing specifically against this, but if it was the case, the use of the specific telephone box (the most “private” public box to Wallace’s house – others nearby being in public buildings which could make them less suitable for a criminal enterprise) is no longer neatly explained. The idea of a “stakeout” was introduced to explain the usage of that particular box and the rough dovetailing of the time of the call with the time Wallace left his house that night. A person who was not staking out the Wallace house could place their call from any telephone box in Liverpool.

If a person did not watch Wallace leave his house but knows when matches generally start, speaking to the café at 7.20 PM poses a significant risk that Wallace will already be at the club. By the publicly listed match time on the noticeboard it is only 10 minutes before matches are set to begin. Speaking to Wallace directly would increase the chances of the plan failing because it gives Wallace the chance to question the caller on the odd details and how he came to know he plays chess at the café. It is also likely that anyone who is familiar enough with Wallace to know all the necessary details to conduct the crime would also have a voice that is familiar to him (we know that Gordon Parry’s was), just as Wallace’s voice is familiar to Beattie.

Of course it stands to reason that if a third party was truly hoping to speak to Wallace on the phone, it wouldn’t be ideal to place a call before Wallace is due to be there. And with such a third party clearly not actually being busy with his “daughter’s birthday party”, it would have been possible to accept Beattie’s suggestion to call back later when Wallace would be there.

C) That someone by happenstance was passing Wallace and decided to place the call, most likely as a prank as speculated by P.D. James.

This requires a lot of advanced knowledge of Wallace and his movements. A person would need to be aware, as above, that William went to the chess club on a Monday and the rough time he tended to show up. Knowledge not definitely ascribed to many people outside of Julia and members of the chess club, or someone who has specifically studied the café noticeboard which would unlikely be the case when discussing an opportunistic prank call.

As previously mentioned, Gordon Parry has not been shown to have knowledge that the chess club meets on Monday evenings.

—

The only known individuals with proven knowledge of the dates the club meets, and the time matches start/time Wallace is likely to arrive, is a chess club member or Wallace himself. The publicly posted noticeboard can easily fill in these details but the individual(s) using the noticeboard would also need to have the information necessary to carry out the robbery the following night – which includes Wallace’s home address (a detail some members of the chess club like Beattie did not know), and where the cash box was kept in Wallace’s house (atop a high shelf in the living kitchen).

The only fitting alternate suspect we know of is Parry, whose plausibility as mastermind was covered earlier.

—

Trams:

The timing of the trams running to the club were rigorously described and tested, and the distance between their stops measured in distance by P. Julian Maddock. These tests are displayed here.

It should be noted that it is possible if the phone in the box went down even as late as 7.26, for Wallace to walk to the Belmont Road tram stop (6 minutes at an average walking pace – arriving at the stop at 7.32), board a tram there with no wait time and arrive at the City Café at 7.50. This is the time he initially claims he arrived at the club. The phone is generally agreed to have gone down earlier than 7.26 (around 7.24 to 7.25) which makes the trip more comfortable and even allows for a couple minutes waiting for the tram all the way over at Belmont Road (trams came every 8 to 9 minutes, meaning a 4.5 minute wait is average). Getting to the club after the phone goes down within the 7.45 to 7.50 window is trivial from the stop near the call box and possible using the Belmont Road stop.

Although his boarding at Belmont Road (even if he made the call) is possible, it is of importance that his route on the chess club night is the only route he shows uncertainty about in his statement. He gives detailed, accurate routes and times for all journeys he took on both days, including trips out to Clubmoor and back for his insurance rounds (both morning and evening collection rounds), but not for his trip to the chess club:

“When I left home of Monday night to go to the Chess club I think I walked along Richmond Park to Breck Road and then up to Belmont Road, where I boarded a tram car and got off at the corner of Lord Street and North John Street.” – William Herbert Wallace

This statement helps to place him farther away from the phone box, while failing to commit provides him with an “out” if anyone comes forward and says they saw him at a different tram stop.

Expert tram testimony: From Robert Morris of the National Tramway Museum:

“Thank you for your message. It is difficult to answer this definitively as there are lots of factors that would affect the case such as the type of tram, how busy it was, how observant the conductor was and where they were when the passenger boarded the tram. Most trams were operated in a similar way to buses and the passenger would board the tram, find a seat and wait for the conductor to approach. They would then state their destination and purchase a ticket. As this took time it is conceivable that a passenger could get on and off without being observed by the conductor, particularly as the journey in this case was quite short [between the stop William claimed to get on at, and the one the prosecution alleges he boarded at]. In the 1930s Liverpool operated double deck trams so the conductor could have been upstairs and not seen the passenger and the driver would probably have been concentrating on the road ahead.

I realise this is quite a vague answer but I think it is safe to say that he could have boarded the tram at a different stop and no one would have noticed.”

There are two additional stops between the stop near the phone box “Qualtrough” used and Belmont Road. Even a Wallace who did not place the phone call would pass these by, and since it is a long straight stretch of road, he would quite easily be able to look back and see if a tram was approaching (from the phone box direction) as he made his way to Belmont Road. If he arrived at a stop and did not see a tram coming he would then walk to the next one. By the time he reached Belmont Road, if no trams had yet been past at the earlier stops, one would be arriving there shortly. He would also be able to see trams pass by from the telephone box during the call.

Assuming the average walking speed of 3 mp/h we can deduce the walk time between each stop:

- The distance between the phone box and Richmond Park request stop is 233 yards, about a 2½ minute walk.

- The distance between the Richmond Park request stop and the compulsory Newcombe Road stop is 157 yards, about a 1¾ minute walk.

- The distance between the compulsory Newcombe Road stop and compulsory Belmont Road stop is 133 yards, about a 1½ minute walk.

The entire stretch from the telephone box to the Belmont Road stop is 523 yards, about a 6 minute walk at this average pace. There is even slight leeway depending on walking speed if he did walk across to Belmont Road. For example, a pace of 3.5 mp/h makes it a 5¼ minute walk, and 4 mp/h makes it 4½ minutes. If Wallace was trying to create as much distance between himself and the box as possible when boarding a tram, he may have walked at these brisker paces. For a man as tall as he was, stride length would make brisker walking paces more comfortable.

(Measurements by P. Julian Maddock

Walking times derived from CalculatorSoup).

Although this map shows the murder night journey, the tram stops in question can be seen at the left of the image.

Wallace made comments about how he “might have” stopped on his trip to the chess club to post a letter at the post box opposite the Breck Road library. Since this post box was near the request stop at the top of Richmond Park, it could be speculated that he waited and boarded there instead, and the mention of mailing a letter was to excuse any sighting of him hanging around that area while waiting for the tram.

Because he did not fully commit to the route he took to the chess club, mailing a letter could also be used to explain why he had gotten on at a different stop if a witness claimed to have seen him board there. He would be able to claim that he usually would have taken the route stated, and simply forgot he had boarded at Richmond Park instead after stopping to mail the letter.

To reiterate: It is possible for Wallace to make the “Qualtrough” phone call and reach the chess club within the stated window of time, even by using the tram stop at Belmont Road which he claimed to have boarded at.

The Voice:

The first person at the café to speak to “Qualtrough” was waitress Gladys Harley, who described the voice as strong and deep, yet ordinary. The telephone operator Lillian Kelly heard the voice speak to Gladys and did not note any sudden shift in the voice, so it would seem the voice remained the same when speaking to the telephone operators and Miss Harley.

Lillian Kelly states:

“I listened on the line for a moment with a view to ascertaining if he got the right people. I heard him say “Is that the City Cafe” and receive the reply “Yes”. I then went off the line.” – Lillian Kelly

It should be noted that Miss Kelly stated the voice was not gruff, which contrasts with the voice Beattie reported hearing:

“The man spoke with an ordinary voice, certainly not a gruff voice and appeared to be a person accustomed to using the telephone.” – Lillian Kelly

This is corroborated by the first operator Louisa Alfreds:

“The voice was quite an ordinary one and appeared to me to be that of a man used to using telephones. It was decidedly not gruff.” – Louisa Alfreds

It is significant that only Beattie described the voice as being “gruff”. This could suggest that the individual on the phone was familiar with Beattie and was attempting to disguise their voice. Because the individual on the telephone did not ask to speak to Beattie, and instead it was Miss Harley who got him to come to the phone, it is possible the voice did not expect he would have to speak to Beattie.

Of note, despite Wallace and Beattie attending the same chess club it does not appear as though they had ever spoken much before and were evidently not close friends, as Beattie states: before the murder he did not even know what Wallace did for work. It is also worth considering that Wallace was just recovering from a bout of flu, and his voice may have sounded a little different as a result.

Accent:

Some might speculate that the fact the man had an ordinary accent (ordinary to Liverpool locals) precludes the Cumbrian Wallace from being the caller. However, while Liverpool-man Munro was still alive he was quizzed on this very thing and confirmed that Wallace did not have any sort of regional accent, so this cannot be used to rule him out.

It may sound incredible in the 21st century to hear that a non-Liverpudlian could pass as local by voice, but in 1931 the Liverpool accent was far more neutral and very different to the thick modern day “scouse” accent.

—

Knowledge of the Club:

The City Café noticeboard was visible to the public and therefore could have been used to determine when Wallace was due to attend the club. The same noticeboard contains a list of tournament rules where the match start time of 7.30 is shown.

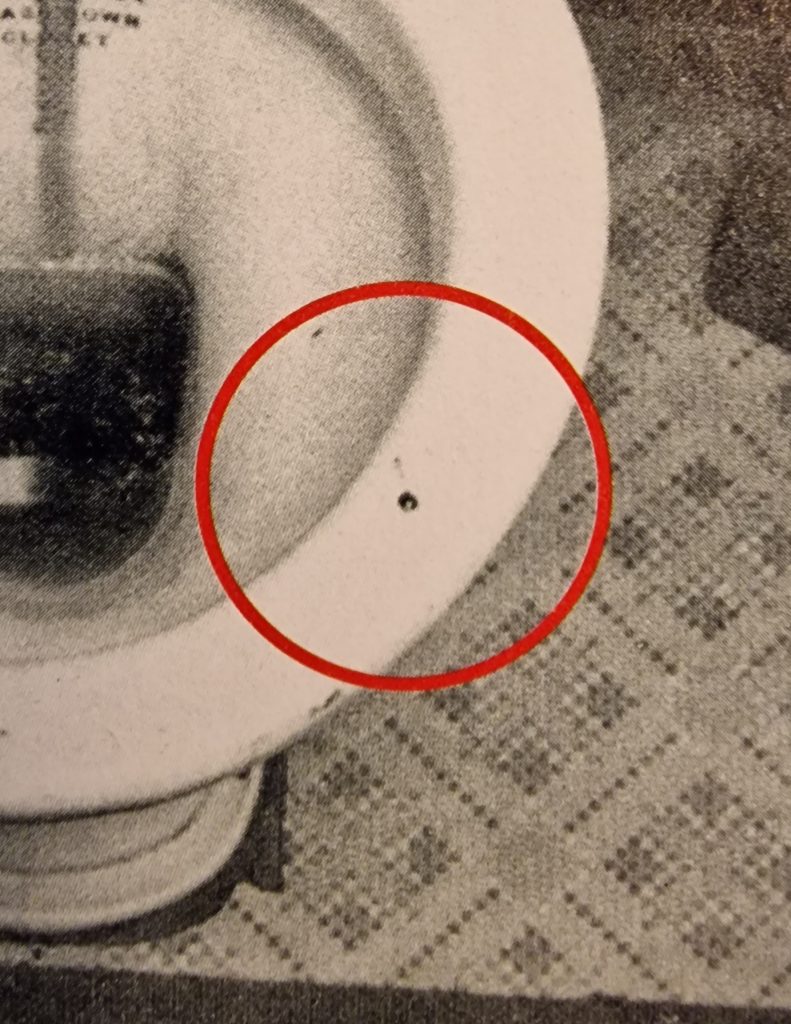

The match listing chart is photographed here:

To explain the chart it is as such:

Each player is assigned a row number. The numbers in the columns coincide with a row number, indicating scheduled match-ups. The crosses indicate days when the person did not have a match scheduled and would therefore not be due to show up. A ‘W’, ‘L’, or ‘D’ beside a number would indicate that the match was played, with the letter corresponding to the result (Win, Loss, or Draw).

However, Wallace was not the only member of the club who was liable to no-show. In fact, on the 19th of January when the “Qualtrough” call came through, Wallace’s opponent did not attend the club, and thus the chart result above appears as though Wallace did not show up – when it was actually his opponent who failed to attend. Vice versa if we look at his previous scheduled matches where he failed to show up, we see the man he was due to play also has no letter by the number in the column, which by the logic suggested by some authors would mean they also did not show up.

So in reality details about the regularity of a member’s attendance cannot be known from the chart, even if a person wanted to figure this out.

For Wallace’s chess division, all match games were played on Mondays, but we know that he attended on at least some Thursdays. According to Wallace, Parry had seen him there playing chess on a Thursday in November, and Parry confirms three sightings of Wallace at the chess club during his own drama club rehearsals (Thursdays). William claims that he would often set aside time roughly every other week to go to his chess club, irrespective of whether or not there was a match scheduled.

The café could expect around 100 visitors per day according to waitress Gladys Harley, so there are many people who could have seen this noticeboard which gives the match dates to anyone who knows “W. H. Wallace” is William, and a match start time of 7.30 PM as shown on the club rules notice beside this (shown earlier).

The actual question to ask would be why the perpetrator did not carry out the crime on the night of the chess club, or why they didn’t leave a note at Wallace’s home.

Why not simply put a note through William’s letterbox?

“Mr. Qualtrough” clearly knew where William lived and was within 400 yards of the home at the time the call was made. He therefore had a surefire way of ensuring the message found its way to William: by posting a note through his letterbox.

The issue with a note is that it would remove the element of corroboration provided by a phone call. A phone call involves several more witnesses who can come forward and attest to the fact that a message really had been called through on a certain day. The alleged difficulty patching the call through increases the odds of corroboration from operators at the telephone exchange, who would be more likely to remember putting the call through to the cafè.

It has been said that a third party might want to pretend there had been a mix-up in the relaying of the telephone message, and turn up to Wallace’s house claiming to be “Qualtrough” there for the appointment. However, it is important that the caller asked for Wallace’s home address and Beattie failed to provide it to him. A true third party caller would have no way of knowing that this detail was not passed on to Wallace (and from him to Julia), which would make it difficult for such a person to explain to Julia how they came to show up at the house.

Elements of the Message:

If Wallace called this is a dangerous part of the plan as he risks his voice being recognized, even if the recognition only occurs in retrospect after the murder.

It has been speculated that asking Samuel Beattie for Wallace’s address means Wallace called, since who but Wallace could be sure that Beattie would not know his address? This assumes that the caller did not want Beattie to supply them with this information. While it can be said that asking for the address may be Wallace attempting to further obfuscate his identity to Beattie, it is also true that Beattie giving the address to the caller provides a possible benefit: When the crime occurs the next day and the police investigate the matter, they are going to come to the conclusion that this was a person who possibly did not even know where Wallace lived until Beattie told him.

The “Alibi” Appointment

Apparently the sole purpose of this call is for William to create an alibi for himself and a red herring for detectives to chase. The details chosen for the bogus call can offer insight into the intentions of the caller.

The Name – R. M. Qualtrough:

It is interesting that the similarly named R. J. Qualtrough is a real Prudential client, and some years ago had been a client of a man Wallace had supervised: Joseph Caleb Marsden. Marsden was named by Wallace as one of his prime suspects alongside Gordon Parry, and according to Wallace he had been fired from the Prudential for financial irregularities. Marsden also knew Parry, and it was Parry who suggested Wallace give him work when he (Wallace) was ill in bed some years prior.Here are some possible reasons behind the use of the name “Qualtrough”:

- A third party such as Marsden or Parry is trying to frame R. J. Qualtrough.

- It is something the person thought up as a random name on the spot or from somewhere else entirely.

- Wallace purposefully wants to frame a Prudential worker, apparently Marsden or a friend of Marsden (such as Parry) for the murder.

- A person is trying too hard to make the call seem bogus. Or trying too hard to impress the details into people’s minds.

Giving the name of a non-existent man (R. M. Qualtrough) helps to push the notion that the message had been left with ill intent, and not by a genuine caller. The use of an unusual name means a person is likely to ask for the spelling, and this would further cement the name (and thus also Wallace in the course of his Menlove inquiries) into a person’s mind. The police officer Wallace quizzed in the Menlove Gardens area confirms that Wallace spelled out the name to him; he does not mention having asked him to do so.

There is risk for a burglar in choosing a real client’s name if William knows of the man, tells Julia about him, then someone goes to the home pretending to be him – perhaps a 20 year old when the client “R. J. Qualtrough” is 50+. This is also true from the details of the message, which imply they wish to take out a policy for their daughter’s 21st birthday: It would be incredibly difficult for someone around Gordon’s age, or even Marsden’s age, to show up at the Wallace house claiming to be this client.

The Address – 25 Menlove Gardens East:

Menlove Gardens East is quite extraordinary in the fact that while there is a Menlove Gardens North, South, and West, there is no East.

But much like the strange name, a fake address is not necessary to form an alibi. The entire point of an alibi is simply to show that you are away from your home at a certain time. While it is true that a fake address allows him to go and talk to a great number of strangers, the round trip in and of itself is a touch over an hour. He only really needs to go to 25 Menlove Gardens West, perhaps check a directory at the newsagent’s “in case a mistake had been made”, then return home.

The use of a fake address would instead be born of an “overthinking” mind, to play up the angle that it’s an insidious phoney message carefully constructed for criminal purpose. It furthers the perception that the call was intentionally malicious and not just an honest mix-up.

Additionally, a false address means Wallace has an excuse to impress himself upon a large number of people on his trip to Menlove Gardens. As we can see, he is told several times that the address does not exist, and remarks as such to resident Katie Mather of 25 Menlove Gardens West, but continues making his inquiries.

For a burglar a fake address only lowers the odds that Wallace will go on the trip: the round trip of an hour to Menlove Gardens WEST and back would be ample time to commit the robbery and escape.

The ABSENCE of an Alibi?

Richard Gordon Parry’s alibi for the day of the call, and the statements of his girlfriend Lily Lloyd and her mother which prove this to be false, are provided below:

Gordon Parry’s Statement:

…On Monday evening (19 January 1931) I called for my young lady, Miss Lilian Lloyd of 7 Missouri Road, at some address where she had been teaching, the address I cannot remember, and went with her to 7 Missouri Road at about 5:30pm and remained there until about 11:30pm when I went home.

This statement was officially recorded on the evening of January 23rd, 1931, three days after the murder, but Parry stayed there through the night going through and giving his full statement before signing it in the early hours of the following day (the 24th of January).

Lily Lloyd’s Statement:

…On Monday 19 I had an appointment at my home with a pupil named Rita Price. I cannot remember properly but either Rita was late or I was. It was not more than 10 minutes. I gave my pupil a full 45-minute lesson and about 20 minutes before I finished Parry called. That would be about 7:35pm. I did not see him and when I finished the lesson he had gone. I know he called because I heard his car and his knock at the door and I heard his voice at the door. I do not know who answered the door. He returned between 8:30pm and 9pm and remained until 11pm. He told me he had been to, I think, Park Lane.

For the record, Park Lane is just a little over one mile from the café where Wallace was attending his chess club. The chess club is on a main strip of the town at North John Street. South John Street is a continuation of this same strip, then below that there’s Park Lane. The café where the chess club met is a public café. This could seem suggestive but it is contradicted by Lily’s mother who actually spoke to Gordon face to face.

Lily is simply reporting what she overheard him say to her mother at the door (prefacing the name of the road with an “I think”), while she herself was at the piano with a student. Lily’s mother’s statement is as follows:

Lily Lloyd’s Mother’s Statement:

On Monday 19 January 1931 Mr Parry called at my house at about 7:15pm as near as I can remember. I can fix the time as about 7:15pm because my daughter has a pupil named Rita Price of Clifton Road who is due for a music lesson at 7pm or a bit earlier every Monday. Last Monday (the night of the Qualtrough call) she was a few minutes late and she had started her lesson when Parry arrived in his car. He stayed about 15 minutes and then left because he said he was going to make a call to Lark Lane. He came back in his car at about 9pm to 9:15pm and stayed until about 11pm, when he left.

In addition to saying he went to “Lark” Lane rather than Park Lane, Lily’s mother claims Gordon arrived at a time which would make it impossible for him to have placed the phone call to the café. However, Lily’s mother also bases her estimate of the time on the arrival of Lily’s pupil Rita, and does not imply she has any knowledge that Rita had in fact turned up 10 minutes late. If she was basing her time judgement on Rita’s arrival time, it would adjust her estimate of Gordon’s arrival to 7.25. She also states 7.15, a “round” number one is likely to use to provide a general idea when they don’t know with certainty (these sorts of times are seen in the Prudential client statements: X.15, X.30, X.45 and so on).

Being a music teacher engaged in a lesson with a pupil, Lily Lloyd is likely to have been more aware of the time. Especially since Rita was late and it is likely she would have been checking the clock while waiting for Rita to turn up. A music teacher has to know how much time is left in a lesson so they can cover the things they want to cover, and to make sure they are finished by the time their next student is due. Some piano tutors will keep a clock on top of the piano to help them with this.

I would suggest accepting Lily’s mother’s naming of the road “Lark Lane”, and Lily Lloyd’s stating of the time.

The false alibi:

Based on this testimony, we can see that Parry did not go to Lily Lloyd’s house “at about 5:30pm and remain there until about 11:30pm when he went home”, meaning the alibi he gave to the police is false.

There are a few possible reasons for this:

- He made the telephone call or was with the person who did.

- He was engaging in some other criminal act at the time.

- He had no good alibi for the time.

- He is protecting someone else he believes could be wrongly implicated or harmed by providing an accurate alibi.

- He had been engaged in a private or embarrassing activity during the time in question, and was hesitant to disclose this to the police. This is especially true if he did not grasp the relevance of the Monday night events.

- He was not prepared for questions about his activities on the day of the call, leading to a hasty or inaccurate response. But for the day of the murder, he may have been more ready to provide a detailed and accurate account.

There are also a couple more possibilities but the fact he gave such an accurate account of his movements on the Tuesday could preclude them:

- He genuinely believed he had been with Lily Lloyd as he stated.

- He felt intimidated/stressed, leading him to provide inconsistent or inaccurate information.

It is noteworthy that his false alibi “blocks out” a very large period of time rather than the specific window of time in which the call took place.

If Gordon was not the caller and thus had no idea when the telephone call was made, or which telephone box was used, it makes sense he might try to take out such a large period of time. An innocent Gordon could not be certain if he was engaged elsewhere at the time the call was made, or if he was instead driving about or passing by telephone boxes. He could believe that blocking out a large window of time like this protects him from this danger.

There are many possible speculations surrounding this lie, but what can be said in addition to the above, is that historically speaking the list of murder cases where suspects gave false alibis for their whereabouts at a particular time, but were later proven to be innocent via things such as DNA evidence (or the real killer being caught), is extremely long. In most instances it turns out the interviewed suspect was engaged in some other activity at that time which they did not feel comfortable admitting to, like cheating on their girlfriend. As mentioned, if Gordon did not grasp the significance of the Monday night, he would be far more likely to lie if something like that had been the case.

Other cases where a false alibi was provided by a later-cleared suspect:

For examples of other suspects who provided misleading alibis to police but were later cleared of involvement, you can see:

- Rachel Nickell murder:

Colin Stagg misrepresented parts of his story to avoid suspicion. Later cleared when Robert Napper was charged with the crime based on DNA evidence. - Lynda Mann and Dawn Ashworth murders

Before Colin Pitchfork was proven to have committed the killings, Ian Kelly gave a false alibi to cover up the fact that, at the time in question, he had been committing a robbery. - Rosemary Anderson murder:

John Button gave a false alibi due to fear and panic, but it was later proven that serial killer Eric Edgar Cooke was responsible for the crime.

These are just some examples out of a very lengthy list.

Summary of the “Qualtrough” call:

Anfield 1627: The phone box from which the “Qualtrough” call was made. A 4½ minute walk from Wallace’s house.

Conversely, the details do not show any eagerness for the victim (Wallace) to take the bait, considering that a real address like 25 Menlove Gardens West would be less likely to arouse suspicion, while still luring the victim away from the home for at least an hour if not more (more than enough time for the robbery). By picking a fake address, the fake nature of the message could be discovered with even the slightest effort, for example by checking a map.

It can be seen that a fake address is not necessary to form an alibi, nor is it necessary in luring a victim away from the house for the amount of time needed to comfortably rob the home (and in fact it works against that aim).

The only gain from using a fake address is to play up the false nature of the message and thus the insidious intentions of the alleged burglar “Qualtrough”, and to provide an excuse to ask a large number of people for directions.

Many aspects of this crime show signs of heavy overthinking, and suggests the plan is from the mind of someone who has been reading too many novels or has no real “criminal intelligence”. In the mind of its creator it may have seemed clever, but actually serves to make Wallace look guiltier than he otherwise might.

If William was guilty of this crime, a few more examples of this behaviour would include:

- Stopping a police officer around the Menlove Gardens area and revealing to him the entire story of the chess club, phone message, business client, nature of business, and address.

His excuse for stopping with the police officer and divulging the entire details of the strange call, chess club, client, and so on, was that the officer was friendly. However he is supposed to now be late for an important business meeting, so stopping to chat with a policeman at length betrays the expected sense of urgency. Extract here:

“During a conversation he led me to believe that he was connected with the Insurance business, and was looking for a Mr. Qualthorp, who had rung up the club, leaving a message for him, and giving the address as mentioned.” – James Serjeant

- Bringing up the business appointment to the tram conductors on the journey to Menlove Gardens and telling them both that he is a “stranger” to the area.

- Pretending to mis-hear “East” as “West” when taking down the message from Beattie.

- Bringing up and remarking on the oddity of the name “Qualtrough” to James Caird on the journey home from the chess club.

- Remarking to Katie Mather of 25 Menlove Gardens West: “it’s funny isn’t it, there is no East.”

It is possible he botched the telephone call in the phone box on purpose to impress the caller into the minds of the telephone exchange operators, and thus increase the odds of operators coming forward and providing a rough time for when the call was received. An eagerness to use the time of the call to exonerate himself can be seen in his pressing of Beattie to provide a more accurate time of when he received it. As seen from the questioning of Wallace on trial:

3265. Was it with that in your mind that you asked Mr Beattie if he could possibly remember the time? It was, because Mr Beattie was uncertain and I thought if he could fix it, as he thought it was about 7, that it was 7 o’clock and I left at a quarter past 7, at all events I could not have sent that message.

Speaking to an unnecessary number of telephone operators aligns with speaking to an unnecessary number of witnesses around the Menlove Gardens area and together paints a picture of a man eager to gain an unnecessarily large amount of corroboration.

—

Who Killed Julia?

The only known figure in this case who we can definitively state had all information necessary to conduct this crime, is William Herbert Wallace. Other figures who come close to this would be:- Gordon Parry has almost all necessary information, but it was not established that he had any knowledge of the chess club meeting on Monday evenings. However, this information could be easily gained from the chess club noticeboard (covered in depth earlier on this page). He also has an alibi for the murder from ~5.30 PM to 8.30 PM with several witnesses including Olivia Brine and Harold Denison.

- James Caird who could not have placed the Qualtrough telephone call due to the time he arrived at the chess club, and has no proven knowledge of the location of the Prudential cash box.

An “Accomplice”:

On the note of an accomplice unknown to Julia gaining entry into the home, such an individual has no need to murder her, since she has no clue as to their identity. If they had gotten away from the scene having sneakily thieved from the cash box with Julia none the wiser, the robbery would soon be discovered anyway, and it would be clear that he had been the perpetrator. In other words, if the criminal just took the money and ran, Julia would not be able to identify him any more than if she survived and the robbery was discovered later by Wallace.

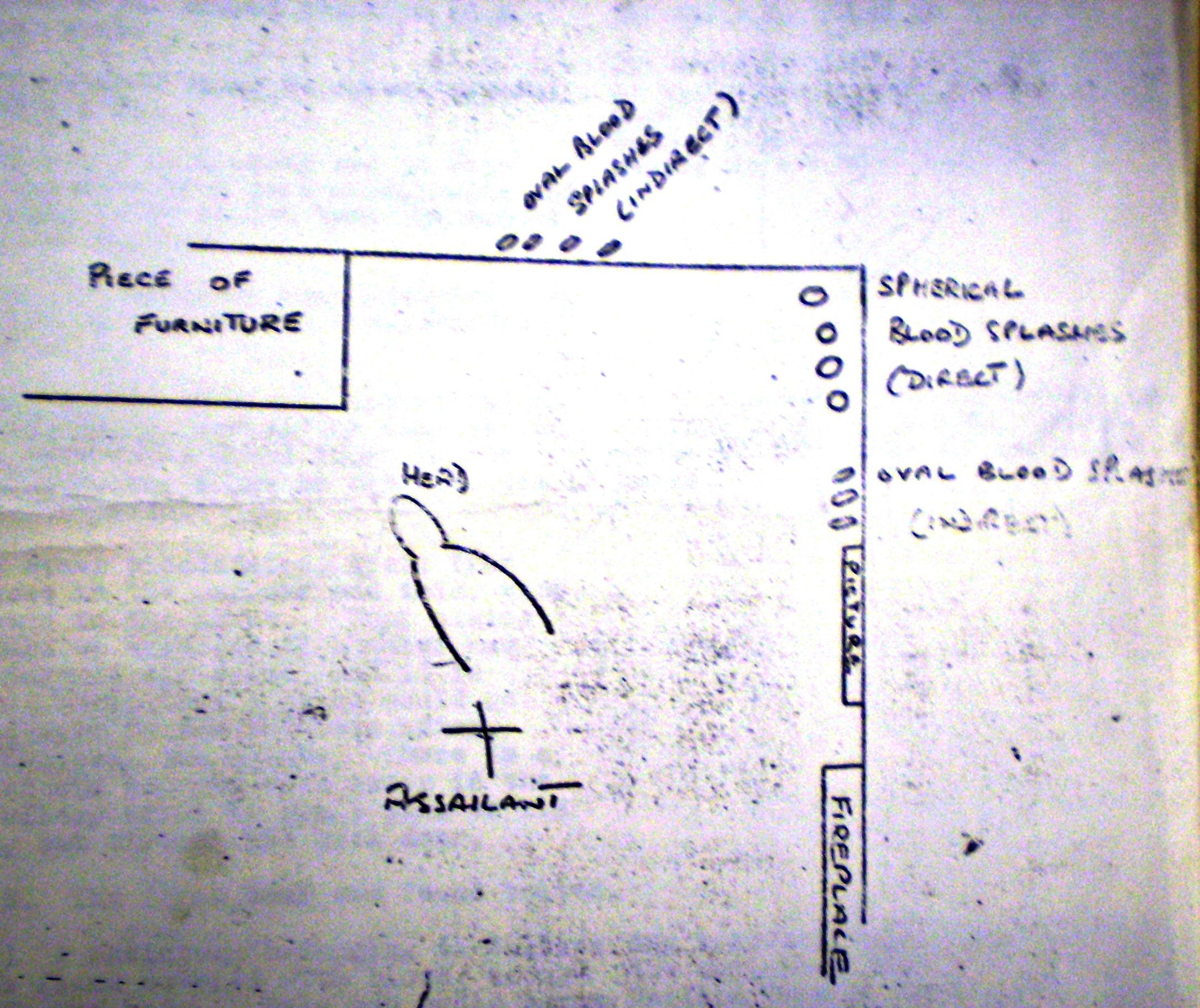

Julia was murdered in the parlour near the fireplace, and evidently had not stumbled upon any intruder rooting through the cash box in the kitchen. It does not make any sense unless there was a plan to enter the home and murder Julia before burgling it. In such a case, the paltry amount of stolen money/items would be surprising, as a premeditated attack would preclude the idea of a rumbled burglar killing her in a panic then running off into the night, abandoning his search for loot.

Car washes and confessions:

The primary element implicating Gordon Parry in the killing of Julia Wallace is the word of John Parkes which was given in the 1980s (see part three of the Radio City show here).“If the glove doesn’t fit, you must acquit!” – Parry’s defence team, probably.

His sordid story broadcast on radio where members of the public were also invited to call in and dish the dirt on Gordon. Since Parry had died he had no chance to respond to any of these allegations. The car wash story which went out on the airwaves contained a confession to murder by Gordon and a mitten soaked with Julia’s blood.

Edited out of the broadcast is a claim that the police had staked out the garage following Parkes telling them the story. This is found in no police report at all (including Moore’s letters to the Chief of Police), nor is his apparent statement about the location of the iron bar that he says he made to them. That itself possibly conflicting with the known fact that storm drains in the “neighbourhood” (the grid the bar was apparently dropped down being about a four or five minute walk from the home, near “Qualtrough’s” telephone box) had been thoroughly searched and turned up nothing.

“the Cleansing Department has conducted a search of street grids of the neighbourhood, and the drains of 29, Wolverton Street.” – Hubert Moore

He claims his story was dismissed immediately and yet simultaneously claims the police staked out the garage. And while they took the time to stake out the garage, it would seem they didn’t bother to check the grid where Parkes told them the murder weapon would be found.

While some witnesses such as Mr. Greenlees went to Wallace’s defence solicitor Hector Munro to give statements, John Parkes – upon being dismissed by the police – apparently did not bother to do so, even when Wallace was sentenced to death and in prison awaiting execution.

If the testimony of Parkes is false or he has added untrue elements to a semi-true story, then Gordon might not have involvement in the murder whatsoever.

Analyzing the story Parkes told on the radio, it seems to have been concocted using various local rumours. E.g. that the weapon was an iron bar and that it was chucked down a grid – there was a rumour that an iron bar was dropped down a grid outside The Clubmoor cinema Lily Lloyd worked at. Parkes’ story is the same rumour but using Priory Road instead. I have received testimony that an ordinary iron bar such as the one proposed to be missing from the parlour, would not produce the patterned injuries found on Julia’s head:

“No matter how I look at it, there is a repeating pattern in several of the injuries which would likely NOT fit a metal bar or crowbar unless there was a patterned surface.” – Dr. Greg Schmunk

The description of the missing bar and poker by the maid Sarah Jane Draper:

[the missing poker] was about 9 inches…it had a small knob on it.

[The missing iron bar] was about 1 foot long and about as thick as an ordinary candle

John Parkes did not come to Wilkes’ team with this story voluntarily, instead someone he had told the story to guided them to Parkes. Originally this man “Thompson” demanded money for the information but Green refused and instead they went about hunting down the garage themselves. Upon finding the garage (by picking one close to Gordon’s old house) and learning Parkes’ name, they showed up at his hospital ward with a tape recorder. At this point it is likely Parkes felt pressured into maintaining the story. Dolly Atkinson when first approached made no mention at all of the most critical and shocking elements of this tale, those being the confession and blood soaked glove. Instead, she only mentions a car wash:

“I remember Mr Parkes telling me and my husband about being forced to wash the car. He told us all about it the morning after. I’ve known Mr Parkes for many years, and he certainly wouldn’t make up a story like that.”

It is significant that in Parkes’ recounting of the story, he mentions a police officer visiting his garage before Gordon arrived and telling him Julia Wallace had been killed. As soon as the officer tells him about the Wallace incident, Parkes says: “Wallace? That’s Parry’s friend!” We can gather from this, that even before Gordon turned up at the garage Parkes was beginning to think of him in connection to the murder. This means that if Gordon did arrive after this for a car wash, Parkes may have been suspicious of him and could have misconstrued his behaviour.

It is interesting that the Radio City team had to ask Parkes’ son for permission to talk to Parkes, as it could suggest he was mentally compromised in some way at the time. The nature of the ward he was in was not given.

The Parkes story is entirely uncorroborated by any known fact, and because Parkes was alone when Gordon allegedly came in, it is also uncorroborated by any other witness. There is no corroboration that any of these events took place whatsoever (even an innocent car wash), let alone in the manner they have been recounted fifty years after the murder.

Other confessions:

Parkes isn’t the only man who claims to have been on the receiving end of a confession to the slaying. Unlike Parkes, this story from a man named “Stan” points the finger at next door neighbour John Sharpe Johnston:

“Stan said that days before Johnston died, he confessed to killing Julia Wallace. He admitted it was he who had made the Breck Road telephone call to the chess club to get Wallace out the house.

Florence had Julia’s cat ‘Puss’ and was supposed to lure Julia next door to get it. Julia’s cat had been missing for days. But John Johnston had surmised that Julia had gone to Menlove Gardens with her husband when he saw them go out the backyard together, because Julia had on a mackintosh. Julia had in fact been walking down the alleyway looking for Puss, and Johnston didn’t see her return.

The Johnstons waited for a while, then slipped into the Wallace’s house via the back kitchen door, which John unlocked with his key. He went in search of the insurance man’s monthly takings and a nest egg he believed to believed to be upstairs. That nest egg, if it ever existed, was nowhere to be seen, and there were no monthly takings because Wallace had been off work with a bad cold and unable to collect the usual amount of money for that month.

Disappointed with the meagre cash they found, John and Florence decided to try the front parlour. As they entered they got the shock of their lives when the flu-stricken Julia Wallace rose from her couch with the mackintosh over her. She wasn’t supposed to be there. ‘Mr Johnston!’ Julia probably shouted, alarmed and then puzzled as to why her neighbours were in her house. John decided to hit her with the jemmy he’d used to smash open the cabinet in the kitchen. He had to kill her, because she now knew the identity of the man who was burgling the neighbourhood.”

These stories when seen side by side offer a stark reminder as to the importance of verifying the credibility of a witness and their testimony. These stories are uncorroborated by known fact and not backed up by any other witness.

—

Lily Hall’s Sighting

Although many people had claimed to have seen Wallace that night (or even people who came forward claiming to have been the murderer only to then be ruled out as impossible perpetrators), Lily Hall’s holds some weight as she lived nearby, knew Julia, and knew Wallace by sight.Lily Hall claims she had seen Wallace speaking to a man in Richmond Park shortly before he arrived back at his house, even though Wallace strongly denied this claim.

I am a typist employed at Littlewoods Ltd, commission agents, Charles Street, off Whitechapel, and I live with my parents at 9 Letchworth Street. I have known Mr Wallace for 3 or 4 years by sight and about a fortnight ago, I learned his name from Mr Johnston, junior, of 31 Wolverton Street. I was there visiting them.

On Tuesday night, the 20th instant, I left business at Charles Street soon after 8 p.m. and took a tram home at the corner of Lord Street and Whitechapel. I got off the tram at the tram stop in Breck Road at the corner of Walton Breck Road. I had arranged to go to the pictures that night if I got home in time and when I got off the tram, I looked at Holy Trinity Church clock, which is near the tram stop, and saw that it was then 8.35 p.m. by that clock.

I came straight home along Richmond Park and as I was passing the entry leading from Richmond Park to the middle of Wolverton Street, I saw the man I know as Mr Wallace talking to another man I do not know. Mr Wallace had his face to me and the other man his back. They were standing on the pavement in Richmond Park opposite to the entry leading up by the side of the Parish Hall. I crossed over Richmond Park and came up Letchworth Street and home. When I got into the house, our clock was just turned 8.40 p.m. but it is always kept 5 minutes fast. It takes me not more than 3 minutes to walk from the tram stop to our house.

The next morning I heard Mrs Wallace had been murdered and when I got home that night, I told my parents that I had seen Mr Wallace the previous night. Mr Wallace was wearing a trilby hat and a darkish overcoat when I saw him talking to the man in Richmond Park on Tuesday night. The man he was talking to was about 5ft 8ins and was wearing a cap and dark overcoat; he was of a stocky build.

A key pointer to the credibility of her statement is that she described Wallace’s outfit correctly, describing it in the same manner the witnesses he spoke to around the Menlove Gardens area did.

There is a further sighting by another individual which helps to bolster the credibility of her statement. This was given to Hector Munro by the witness, but the witness was never called to take the stand. Likely because of this very thing:

Henry Harrison Greenlees of 95 Richmond Park Liverpool will say:-

I am 38 years of age. On Tuesday 20 January last I was returning from a Choir practice at St Georges Church Everton, accompanied by a Mr Leak, my Choirmaster. He left me at Anfield Road. I walked down towards the end of Walton Breck Road, and looked at the Clock of Holy Trinity Church which is brightly illuminated. It was then 8.35 p.m.

I walked along Richmond Park and when opposite No 26 Richmond Park but on the other side I was accosted by a stockily built man in a felt hat who had crossed over from the bottom of Letchworth St. He asked me to direct him to No 54 Richmond Park. I told him that number did not exist.

I know both Mr Wallace and Miss Hall, and did not see either of them that night. It was 8.40 p.m when I stepped into my house.

This aligns with the man Lily claims to have seen Wallace talking to who she also described to be a stocky man in a hat. The fact that she seems to correctly identify the presence of another man who is corroborated to have been in the area at the time, is a strong reinforcing factor in the validity of her statement.

It is likely that Lily Hall truly did see Wallace speaking to this man.

If this man had asked Mr. Greenlees for the non-existent address (54 Richmond Park) and had no luck, he may well have asked others in the area. As proof of this we can see that Wallace asked many people for 25 Menlove Gardens East even after being told it did not exist. This man may have also approached Wallace with his inquiry.

Wallace never mentioned the man because the man serves no purpose to his alibi, and he knows the man did not kill Julia. The man would never come forward because the circumstances of his own inquiry and proximity to the scene of the murder is so coincidental as to look condemning.

To an innocent Wallace, given the circumstances of his own trip out to a bogus address, remembering being approached by a man asking for a bogus address just by his home where he found his dead wife minutes later would be alarming. This would be an individual he should have mentioned to the police when they asked if he had noticed anyone suspicious near his house.

Alan Close’s Sighting

Julia Wallace was in the habit of taking in milk which was delivered to the house from Sedley Street. There were two children who would do these deliveries: Alan Close and Elsie Wright. On the night of the murder, Alan Close (who was running late on the murder night and “hurrying”) told the local children that he had delivered milk to the house at 6.45, and had seen Julia at the doorstep. This sighting was deemed critical, because Wallace claims to have left his house for Menlove Gardens at this time. If his wife was alive and well at the time he left the house, he could not have been guilty of the murder.Alan Close later adjusted the time back from 6.45 to ~6.31 after trial runs with the police, using his sighting of the church clock at 6.25 as a reference point.

His original statement reads:

“Between 6.30 and 6.45p.m. on Tuesday the 20th January 1931 I took Mrs.Wallace’s milk.” – Alan Close

The latter time of 6.45 is refuted within Alan’s own testimony, as he claims to have checked his watch and seen it at 6.45 in Redford Street, which was after leaving 29 Wolverton Street. Because his watch was 1 to 2 minutes fast, this means he would have been in Redford Street at 6.43 to 6.44. It is a three minute walk to Redford Street along the route he says he took (from 29 Wolverton Street, along Richmond Park, and then to Redford Street), which means that by his watch he left 29 Wolverton Street at around 6.40 to 6.41, which would itself be after waiting around 1 to 2 minutes at the open door for Mrs. Wallace to return with the empty milk can.

In other words, nobody places Alan at the Wallace door at 6.45, not even Alan, as can be seen from his statement:

“I then went along Wolverton Street to Richmond Park and then to Redford Street and then went home. When I got to Redford Street I looked at my watch and it was then a quarter to seven. My watch is a minute or two fast.” – Alan Close

Wildman was the oldest witness of the children (16 years old) brought in to corroborate Alan’s sighting of Julia. He told his mother that he had seen Alan on the doorstep of 29 Wolverton Street around 6.35 PM, later adjusting this to between 6.37 and 6.38 based on the time he saw the church clock, which matches closely with the time deduced by Alan’s watch. His statement reads:

“When I passed on the evening of 20th January it was twenty five to seven. Having passed Holy Trinity it takes me about two or three minutes to get into Wolverton Street …I am positive that this was between twenty five and twenty to seven, and not half past six.” – Allison Wildman

In addition to Wildman, Alan’s coworker Elsie Wright stated that she heard the 6.30 church bells sounding and had made a delivery at the vicarage after this (she says they kept her for about 5 minutes), then saw Alan who had not yet reached Wolverton Street.

Wallace’s own statement can help to shed some light on the timing of these events. He claims that upon leaving his house at around 6.45, Julia had followed him down the yard to the back gate. If Julia was in the back yard she could not have also been at the front door taking in the milk or handing the empty can back to Alan Close. Alan says he was waiting for about 1 to 2 minutes at the open door of 29 Wolverton Street for Mrs. Wallace to return with the empty milk jugs, and this was after he had stepped over to the neighbour’s (the Johnston’s) doorstep and left milk in their lobby.

“I knocked at the knocker of her [Mrs. Wallace’s] front door and put the milk in a can on the doorstep. I went to No.31, which is next door and put their milk in a jug just inside the lobby. The front door was open and after putting the milk in the jug I pulled the door to. I went to No. 29 and the milk can had been taken in, the front door was open. In a minute or two Mrs. Wallace came to the door and gave me the empty can.”

During this period of time Julia must have been in the house to hear the knock, take in the milk, and then return to the door to hand the empty can to Alan. She is not during this time out in the back yard. From this we can establish that unless William left significantly before the ~6.45 he claimed, the last known person to see Julia alive is William Herbert Wallace.

Based on all testimony given, an arrival time of the milk boy at 29 Wolverton Street in the region of 6.35 to 6.40 seems perfectly reasonable.

The Window of the Murder:

To be the murderer, Wallace must have left his house after Alan delivered the milk and after committing the murder, and must have done so with enough spare time to board the tram and arrive at Smithdown Lane by 7.06. The tram stop Wallace claims to have used was by St. Margaret’s Church, a distance of 605 yards according to the surveyor.

17 minutes from the back door to Smithdown Lane was established as possible by William Brown Gilroy. 18 minutes was established by Walter Stanley Oliver in company with Harry Bailey, though their test took 20 minutes because they waited 2 minutes for the tram at the St. Margaret’s Church stop.

By the police test it is possible for Wallace to leave his back door at 6.49, board at St. Margaret’s Church tram stop, and arrive at the next stop (Smithdown Lane) in time for 7.06.

The defence team’s witness P. Julian Maddock performed rigorous testing and established an even better time than the police, managing 16 minutes from the Wallace’s back door to Smithdown Lane by the St. Margaret’s Church tram stop. His walk to the tram stop (605 yards) was completed in 5½ minutes, representing a pace of 3.75 mp/h.

“It will be noted that leaving the house at the same time as witnesses Prendergast and Forthergill on Jany.27th. and Bailey and Gold on Jany.26th. vis. 6.45, I apparently caught the same tram at St.Margaret’s Church but arrived at Smithdown Lane at 7.1 p.m. as against their 7.3 p.m. and 7.4 p.m. respectively.”

By Maddock’s tests it would be possible for Wallace to have left home at 6.50. Those tests can be found here.

The tram to Smithdown Lane takes about 10 to 11 minutes, and Wallace claims to have waited 3 or 4 minutes at St. Margaret’s Church to get on this tram. The walk to the St. Margaret’s Church stop is around 5 and a half to 6 minutes. Since Wallace boarded the 7.06 PM tram from Smithdown Lane (he never mentions any wait for this car), we can deduct these times to determine when he is likely to have left his house. Based on these times provided by Wallace himself, he left home around 18½ to 21 minutes before 7.06.

Which makes it 6:45.00 to 6:47.30 PM.

Giving him around five to ten minutes to commit the crime depending on what time Alan left the front door of 29 Wolverton Street. These are Wallace’s own given times.

To get a feel for how long that is, put on a stopwatch and keep watching the time until it reaches these markers. You can also think of it as the length of two songs (the average music track in modern times is 3½ minutes).

It is as long as Foreigner’s hit “I Want to Know What Love Is” played either one or two times through (it is a five minute track), which is very apropos for a domestic homicide.

Details of the Robbery

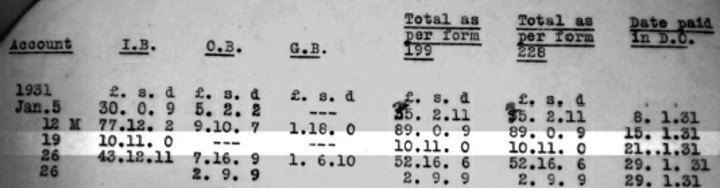

By the disorder in the front room upstairs and blood found smeared on a pound note in the middle bedroom (Wallace is alleged to be the only person known to have handled this money on the night of the murder), it appears that a criminal had gone upstairs at some point during the commissioning of the crime to hunt for valuables.In pre-decimal currency as was used in 1931, money is expressed as £ s d or x-x-x or x/x/x, where £ is pounds, s is shillings, and d is pennies. 12 pennies make a shilling and 20 shillings make a pound. A “half crown” is 2s 6d. Sometimes a hyphen (-) is used to represent a zero, for example £5 17/- is five pounds, seventeen shillings, and zero pence.

According to Wallace, from the cash box they stole the following:

One £1 Treasury note

Three 10 shilling notes

30 or 40 shillings in silver

A postal order for 4s 6d

A cheque for £5 17/-

Total: £10 1s 6d to £10 11s 6d

The cheque could not be used upon being stolen: It was made payable to Wallace from the Prudential company, meaning a burglar would be unable to cash it. Similarly, Wallace would not be able to cash the cheque without being caught if he himself had orchestrated the event and claimed it stolen. Still, a notice was put out on the identity of this cheque whereby police would be notified in the event someone tried to cash it. A notice was also put out on the identity of the missing postal order, and similarly it appears nobody attempted to cash it.

Since neither the cheque nor postal order were ever cashed, we can surmise they were likely destroyed by the perpetrator. This leaves a useable haul of:

£4 to £4 10s.

Wallace paid money into the Prudential the day after the murder, the money he was due to pay in would have been the stolen contents of the cash box. He paid in a total of £10 11s 0d (denoted as 10.11.0). This figure would require adding all the box’s contents, plus taking 35 as an average of the “30 or 40” shillings, and adding upon this the money found on the kitchen floor: a half crown and two shillings. That adds up to a round £10 11s. Without including the half crown (2s 6d), it is not possible to get a zero in the penny column and could suggest an error in Wallace’s accounting. It would then follow that the stated figures of what was stolen would be called into question.

An American dollar bill in the cash box was left untouched, suggesting the criminal either took time to sort through the contents of the box, or did a very perfunctory search and did not discover the compartment the bill was in.

In the middle bedroom upstairs, blood evidence suggests the criminal had found the money in the jar but left it, perhaps due to leaving blood on one of the notes. The amount found in the jar was as follows:

Four £1 Treasury notes

One half crown (2/6)

A postal order for 2/4

Total: £4 4s 10d

Because the cash sum in the cash box and jar are so similar, it could be speculated that the criminal did not remove the money from the cash box downstairs, but instead transferred it (or some portion of it) to the jar upstairs. This would require the perpetrator to have fiddled with the denominations, or Wallace to have misreported them. Indeed it was speculated on trial that the four £1 Treasury notes in the jar upstairs were the £4 of missing money (excluding postal orders and cheques) from the cash box.

Because the postal order in the jar is dated from the 3rd of January and Prudential collections were paid in each week, it is unlikely this postal order had any connection to the Prudential cash box money, and therefore in this speculative scenario it can be ignored.

In such a scenario it would be possible for Wallace to take £4 in treasury notes from the cash box downstairs, along with a half crown and two shillings, then scatter the two shillings and half crown at the foot of the bookshelf to create a look of disorder, before finally going upstairs and depositing the £4 in the bedroom jar where there was already an old postal order and half crown. It would require 60 of the shillings to have been converted to three £1 Treasury notes prior to the murder.

In any case it is significant that at least one pound Treasury note was missing from the cash box, and a pound Treasury note was found in the jar in the middle bedroom with blood upon it. Hubert Moore gave specific instructions that the items in the middle bedroom not be disturbed by those at the scene, and nobody at the scene is known to have touched the notes that night but Wallace. As regards to blood upon his own hands being transferred to the pound note in the jar he states on trial:

3321. Throughout that evening, did you ever find blood on your hands? I did not observe it.

3322. At any time, have you ever said to any human being that you find blood on your hands? I do not think so.

3323. Then so far as you know, no blood from your hands could have got on those notes? Yes, I think I can say that.

And Moore:

“I did not examine the notes W.H.W.27 on the night of the 20th. January. I gave instructions that nothing in the room in which they were should be touched that night.” – Hubert Moore

It is therefore suggestive that the blood on the money in the jar was left by the murderer and not by Wallace or detectives on the scene.

What he missed:

The burglar left behind a half crown and two separate shillings on the kitchen floor near the bookcase upon which the cash box was kept (a value of 4s 6d). This in combination with the four £1 Treasury notes and half crown in the jar upstairs is £4 7s.

The burglar also left Julia’s wedding ring which was on her finger, as well as the brooch around her neck. In the middle bedroom he missed jewellery which was kept in a drawer, and no drawers or cupboards were found open suggesting the burglar had either not checked them or closed them after rifling through them. He missed Julia’s handbag which was on a chair in the middle kitchen where the cash box was kept and this contained £1 7s 16½d.

Considering the blood on the Treasury note suggests the criminal had taken the time to search for money upstairs after killing the woman, it is unusual he had not made a more thorough search and found the other valuables which were within easy reach. It is also curious that the laboratory in the back bedroom was left undisturbed, given it contained expensive items such as Wallace’s microscope.

It is significant that the criminal appears to have gone upstairs after murdering Julia instead of immediately fleeing, as it suggests he was not overly concerned with the possibility of William returning to the house after finding he’d been duped, or the possibility that neighbours had heard any commotion (particularly if it is suggested the burglar had alerted Julia by making a loud noise in the kitchen).

The pay-in day:

Despite a cash value of around £10 11s being missing, Wallace paid this amount into the Prudential the day after the murder. Since the cheque and postal order were never cashed we can surmise these items were not paid in. The police seized the contents of the jar in the middle bedroom so this money was not paid in either. Where this money came from was not clarified.

If he took it out of his personal bank balance by cheque, it could provide reason for wanting to do as little collecting as possible in the week leading up to the murder: Because he may have anticipated paying in the total of the “missing sum” from his own bank account. It would also provide a reason as to why he may have tried to retain some of the “stolen” money such as the bloodstained Treasury note, if this note was in fact transferred from the cash box to the jar and not stolen as claimed.

The expected figure was gathered from Joseph Crewe during the trial, who suggested that the amount due to be paid in for the week of the murder was £30. It is possible Mr. Crewe was not aware that William had been off of work with flu.

989. MR JUSTICE WRIGHT: What about 19th January? The 19th January only £10 11s 0d was paid in, for the simple reason either the police or someone else had taken the cash and the police have a portion of that cash yet.

990. MR HEMMERDE: What makes you say that? Well, I understand the police have at least £18 cash and I have asked for it.

991. What makes you say that; where did you get it from? Because they took, it and I have asked for it.

1004. MR JUSTICE WRIGHT: What ought to be the proper return for the week ending the 19th? The proper return should have been about £30.

This suggests that by skipping work Wallace was able to pay in around £20 less (2/3rds less) than he otherwise would.

It seems very probable that the Prudential would reimburse this money to him given the circumstances, but they might investigate and decide whether the money had been secured well enough by the agent (etc).

Where in the World is Gordon?

Gordon was provided an alibi for the window of the murder, from 5/6 PM to 8.30 PM, by the Brines. This includes Olivia Brine and her nephew Harold Denison. Others were named to have been at the house during this time including Olivia’s daughter Savonna, and a “Miss Plant” who called at an unknown hour.

Some have speculated that this alibi might have been coerced. There is not any proof for this.

Locked Room Mystery

One of the trickier points of contention in the case involves the locks of 29 Wolverton Street. Locksmiths gave evidence on the matter but it is hard to grasp the technical points mentioned.Wallace made a few different claims about the state of the lock. First he claims that upon his first visit to the front door, his key would not turn in the lock whatsoever. He later claimed that the lock was defective, but stated that it had not been faulty before he returned home from his trip to Menlove Gardens:

Q: [Moore] says he tried the key in the lock and opened the door and entered the house. Then he said to you: “I could open the door all right, but the lock was defective”, and you said: “It was not like that this morning”?

A: It was not, as far as I could tell you. I had entered the house on the previous night at about half-past ten, when I came from the Chess Club, and had no difficulty in opening the door.

Further on trial:

3551. Did Mr Moore then try the key in the lock? Yes, I think so.

3552. And found that the lock would turn to a certain point but if the key were turned too far round the lock would slip and the door again be locked? Yes.

3553. In your presence? Yes, that was my own experience.

3554. That had been your experience? On the second occasion on which I went to the door.

3555. And on previous occasions? No; as I said before, never.

And in a statement made to police, he implies this is the first time he found his lock faulty in this manner:

“I tried my key in the front door again and found the lock did not work properly. The key would turn in it, but seemed to unturned without unlocking the door.”

The claim of the lock having recently become defective was refuted by James Sarginson, the locksmith who examined the locks of the front and back doors of the house. He gave a detailed statement describing the faulty condition of the lock:

“I have examined it [the front door lock] and found it very dirty and rusty. The springs were missing from two wards and were not to be found in the lock, they had been broken off for some considerable time. The lock was full of dirt which had not apparently been disturbed for years, and this was the cause of the stiffness in working. There had been no recent damage to the lock. The pin hole was worn big, the key is worn and the part of the lock which operates the latch, and which is operated by the key was also worn and this allowed the latch to slip back to a normal position after the key had been turned just over half way round. Owing to the dirty state of the lock the wards were in a neutral position.”

During the trial he was asked about his opinion regarding the length of time the lock had been faulty in this matter and clarified:

1694. Have you the key there? Yes, the key is here.

1695. Just show the jury? When you put the key in and turn it, it goes right round: this is due to the wear of the lock.

1696. And not to any recent damage, or anything like that? In my opinion, there is no evidence or recent damage at all.

1697. It has been like that for some time? Yes.

On the failure of the key to turn in the lock at all Wallace made the following statements on trial:

3531. What had been your experience with the lock there; that it had just slipped back and would not open? No, I could not make my key turn at all on the first occasion.

3532. Suppose it was bolted, could you make your key turn? Ordinarily, yes.

3533. Then there would be nothing to prevent the key turning; the bolt is in no way connected with the lock? No.

3534. You could not make your key turn? That is so.

3681. Had you ever known before the key not to turn in the lock? No, and we had not been unable to get in with our keys.