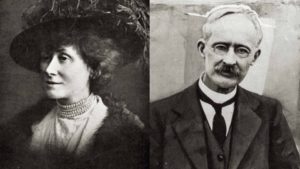

At this time, Wallace works for the Prudential Assurance Company, the originator of the “Man from the Pru” commercials which would go on to make the Pru a household name in later years.

The “man from the Pru” was not just your insurance agent; he was your confidante, a friend, someone you could rely upon for advice. From time to time he could even end up as the designated best man at a client’s wedding… The Prudential agent was sharp and always on the lookout for new business. If a new neighbour had moved in on one of the streets on which he collected, he was expected to take initiative and knock on the door to introduce himself.

Indeed, over the years the Pru gained a reputation for reliability and honesty. Wallace himself had gained a reputation as being a total gentleman, and all who spoke about him gave him a glowing character report (all except an ex-coworker named Alfred Mather*, who appeared to despise both William and Julia Wallace). To most everyone the Wallaces were a very loving, devoted couple. The family doctor and a nurse who had been into the home would attest a sense of callousness between the two, but terraced neighbours the Johnstons said they had never heard so much as a quarrel in a decade of living next door.

[*Cannot find any relation to Katie Mather, resident of 25 Menlove Gardens West]

But in this instance the respectable “man from the Prudential” with the seemingly perfect marriage, William Herbert Wallace, was to be charged with the most heinous crime imaginable: Murder.

But the question still remains: Did William Herbert Wallace really smash his wife’s skull into pieces with a blunt instrument in a cleverly premeditated plan? A jury thought so, and sentenced him to death. But fortunately for Wallace, the judges at the appeal trial saw it differently and quashed his conviction completely, releasing him back into the world a free man. A move which was rather unprecedented at the time. According to Wallace’s solicitor Hector Munro in a rare radio interview (also a member of the Chess Club at which William sometimes played), in that era to overturn a jury murder conviction must have meant that there was not even a “shred” of evidence against the accused.

The intrigue about the Wallace case is that the events seemingly came together so perfectly that it was considered impossible to finger any man as the killer, and so it has remained a Liverpool legend for almost a century – enduring to this day, waiting for someone to finally crack the riddle. Almost every piece of evidence can be seen as consistent with either guilt or innocence, depending on how you choose to look at it.

And the catalyst of this most brutal crime would be a mysterious telephone call to the local chess club on the 19th of January…

THE NIGHT OF THE CALL (19th January, 1931):

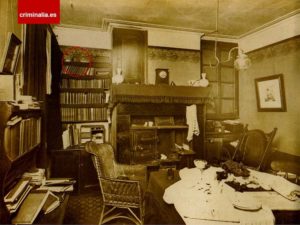

On the night of Monday the 19th of January, William claims to have left his home at about 19:15 – 19:20 to attend his chess club. The club known as the Liverpool Central Chess Club was headed by Captain Samuel Beattie who had known Wallace for eight years. The club would meet in one of the four rooms on the ground floor of Cottle’s City Café, 24 North John Street, to the West of Liverpool near the river Mersey.Although certain “match games” were penned in, these obligations weren’t always kept, and the club would meet every Monday and Thursday evening through the Autumn and Winter months in any case. Wallace was not a “regular attender” according to Beattie, but might turn up once or twice a week. Wallace liked to set aside free time from his insurance work and duties every other Monday, and it was usually on these evenings that he would make a trip down to play a game of chess.

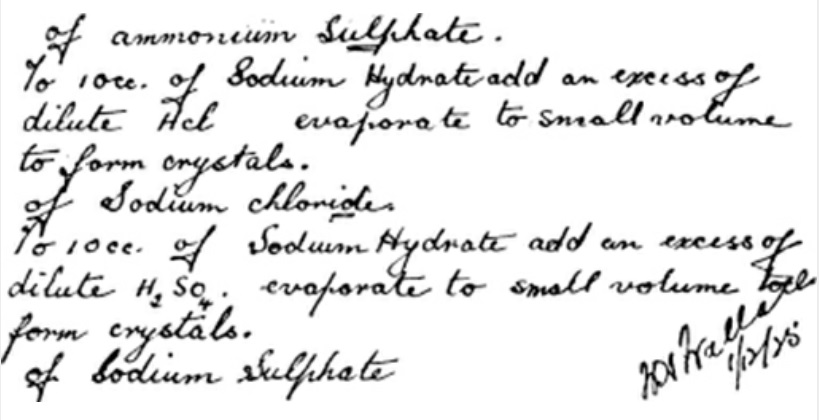

Wallace was a rather studious man with varied intellectual interests which was surely what drew him to the game of chess. Well educated, he had spent time giving lectures in the subject of chemistry at the Liverpool Technical Institute some years prior. Below is an experiment by a student of Wallace’s which he signed. The handwriting is difficult to read to my eye, but it seems to be signed the first of december 1925.

Such was his interest in chemistry, particularly that of a botanical nature, he had a spare back bedroom on the upper floor of 29 Wolverton Street converted into a mini laboratory where he kept various scientific tools and bottles of, presumably, chemicals and specimens.

Other interests of his included philosophy, in his personal diaries he often pored over matters of philosophy with musings about life and death – perhaps in part due to his own constant proximity to death owing to a kidney disease he was repeatedly told would allow him only a few years to live. Although these predictions rarely came to fruition it must have played on his mind, and he had been in hospital on various occasions. It was due to this ailment that he was forced to return from abroad where he had worked in places such as Calcutta.

His brother Joseph Wallace also worked abroad though his wife Amy Wallace had decided to return to Liverpool with their son Edwin where they resided at Ullet Road, Sefton Park. A fortunate turn for William surely, since the introverted type of man that he was, he did not have many friends outside of his wife and neighbour James Caird who lived one street over (Letchworth Street). The visits from his sister-in-law and nephew Edwin would have provided the couple with a social outlet, and they would show this gratitude by serenading them with musical duets in the parlour: Julia, the expert on the upright piano, and Wallace, a relative beginner on the violin.

Much of the household’s money went into these intellectual pursuits, including the purchase of an expensive microscope. Wallace would recall in later life that one of his greatest goals in life was to make some sort of important scientific discovery. Although he unfortunately did not make history through his love of science, he definitely made history in law. His case is still used in Law Schools as a demonstration of a “miscarriage of justice” to this very day.

But aside from chemistry, botany, astronomy, philosophy, and performing music; chess (which he was ironically very poor at given the way this hobby impacted public opinion) was certainly a staple of his. According to Munro, while in the condemned cell Wallace would mostly pass his time reading books on astronomy and playing chess.

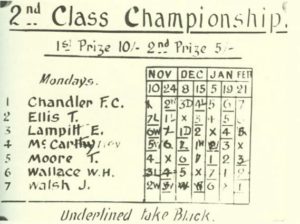

As a second class player Wallace was scheduled to play tournament matches on Mondays (roughly every other week, though the intervals varied), with the match dates displayed on a public chart near the door just outside the Cafés phone booth. Generally up to 100 people could be expected to be in the café, and witness Gladys Harley often waited on the members of the chess club on the nights they met.

Tonight, the 19th of January 1931, as per the schedule displayed on the noticeboard of the café, he was down to play a Mr. F. C. Chandler.

According to Wallace, he was unsure about even attending his club on this night because his wife was poorly with bronchitis and he himself had just gotten over a flu which was sweeping across Liverpool, but she gave him the go ahead – a move which would ultimately lead to her brutal demise.

Things take a turn for the unusual when chess club captain Samuel Beattie receives a telephone call requesting a message be delivered to Mr. Wallace. Although the exact figures are disputed, the call is first attempted from a telephone box in the Anfield district at roughly 19:15 at night.

In those days, telephone calls made from Anfield had to be connected manually by switchboard operators, so the first person this mysterious caller speaks to is telephone operator Louisa Alfreds. According to her court testimony, she successfully put this call through to the café (telephone number “Bank 3581”) and heard a voice pick up on the line. Her friend Lillian Martha Kelly says that Louisa then told the man: “Go ahead please,” which was the cue for the caller to press Button ‘A’ to deposit the coins and connect the call.

But something strange happened… Moments later the man was back on the phone to the operators, this time speaking to Lillian Martha Kelly. She recounts this fateful telephone call many years later in the 1980s:

“…A moment later he (the caller) was back on to the exchange and this time I took the call. He had obviously pressed the wrong button [button B instead of button A] and had cut himself off. The reason I remember it is because he’d pressed the wrong button and had paid his money, but not received his correspondent. I said to Louisa Alfreds who was sitting next to me that this man had just been on before…”

The voice protested to Miss Kelly: “Operator, I have pressed button ‘A’ but have not had my correspodent yet.”

(To add to the mystery, in spite of the first operator claiming someone at the City Café picked up the line, waitress Gladys Hardley strongly disputes this).

The exact order of events here is often written differently depending on where you look, but from the unabridged trial in the Home Office records, Miss Kelly states she was able to see that Button ‘B’ had been pressed and the coins had been returned to the caller by the light on her switchboard – whether this was before or after she had asked him to do so was not made clear enough to be definitive on the matter. Either way she then attempted to connect the call again, but found the line engaged.

Upon failing to connect the call, Miss Kelly flagged down her supervisor Annie Robertson. Telephone protocol meant that any potential technical faults such as this would be noted down, which Annie Robertson did dutifully, writing down the identity of the phone box “Anfield 1627”, 19:20 as the time the call was finally patched through, and an N.R. (No Reply) in the margin to indicate the type of error.

Waitress Gladys Harley answered the phone to the sound of the operator: “Bank 3581?”. Gladys replied in the affirmative. “Anfield calling you. Hold the line.” As Miss Harley waited for the caller to begin speaking (according to her, about 2 minutes after she answered the phone, which would make this around 19:22 at this point), she heard mumbling and something about two pennies – and then suddenly a man’s voice began speaking to her.

When recounting this voice, all of the operators described it as an “ordinary man’s voice, not nervous or agitated”, but perhaps somewhat cultured. One thing that stood out to them was how the man pronounced the word café with the accented “e” (caff-ay), as opposed to the more common “caff”. Gladys Harley noticed nothing unusual about the voice except that it was deep and spoke quickly, and that it seemed to her to be an elderly man. Although she knew Wallace by sight from her time waiting on the chess club, she did not know his voice well and did not know his name, and did not recognize whichever voice was on the telephone.

After the voice asked if he was speaking to the Central Chess Club, receiving a positive response, he asked if Mr. Wallace was there. As a result of this inquiry Gladys went to the captain of the chess club Samuel Beattie to ask if Mr. Wallace was there as there was a man on the telephone wishing to speak to him. Beattie saw that he was not, and at Gladys’s request went to the phone himself.There have been many different variations of this conversation reported by Beattie, but from what can be gathered, the general gist is something along the lines of:

Caller: Is Mr. Wallace there?

Beattie: No.

Caller: Can you give me his address?

Beattie: I’m afraid I can’t.

Caller: But he will be there?

Beattie: I can’t say. He may or may not. If he is coming, he will be here shortly. I suggest you ring up later.

Caller: Oh no, I can’t, I’m too busy; I’ve got my girl’s twenty-first birthday party on and I want to see Mr. Wallace on a matter of a business. It’s something in the nature of his business.

The caller then asks Beattie to pass on a message to Mr. Wallace for him, requesting that Wallace visit him the following night at 19.30, giving his name and address as:

R. M. Qualtrough

25 Menlove Gardens East,

Mossley Hill

My. Beattie then repeated the name and address back to the caller, requesting the name be spelled out and the address repeated back to ensure its accuracy.

At around 19:45 to 19:50 William arrived at the chess club. According to Samuel Beattie there is a rule at the club that those who arrive after 19:45 can be penalised, with matches sometimes starting earlier than this time. It was not stated if this rule also applied to unscheduled matches. Despite these claims, the noticeboard upon which the chess club schedules were posted (the one “Qualtrough” is alleged to have studied) contains a notice stating that games must start by 19:30. If a player is later than this, their clock is started against them. In chess, there is a time limit for each player in a game, and if their clock runs over time, their opponent can call it and win the match. The evening’s matches were to be concluded a little after 10 PM.

Wallace’s opponent F. C. Chandler did not show up that night, so James Caird who had seen Wallace arrive offered him a friendly game. Wallace refused this match (James Caird was in a higher chess league than Wallace), instead settling into a tournament game against a Mr. McCartney who he had previously missed a match with and needed to play off. James Caird then walked over to Mr. Beattie’s table. When Beattie noticed Caird he asked him for William’s address, only to be told that Wallace had in fact arrived at the club and was just about to start a match against McCartney.

Upon hearing this news, Beattie approached Wallace (who seemed very focused on the game) and relayed the strange message to him after rousing his attention. Wallace seems puzzled:

William: Qualtrough? Qualtrough? Who is Qualtrough?

Beattie: Well, if you don’t know who he is, then I do not.

William: Is he a member of the club?

Beattie: No.

William: I don’t know the chap. Where is Menlove Gardens East? Is it Menlove Avenue?

Beattie: No, Menlove Gardens East.

William: Where is Menlove Gardens East?

Beattie: Wait a moment, I’ll see whether Deyes (another member of the chess club who lived in that district) knows (he did not).

A schedule showing the dates players are due to attend the club. This was displayed very publicly on a noticeboard at the café.

Beattie knew of Menlove Avenue West (sic) but not Menlove Gardens East. Deyes had heard of Menlove Gardens North, South, and West, but had not heard of East. But it was agreed upon that it would surely be somewhere off Menlove Avenue which Wallace was advised of. McCartney asked for Wallace’s address so as to suggest a suitable route he could take, and others chimed in with their own suggestions.

Wallace, however, confidently stated that he “belonged to Liverpool” and could inquire once he got into the general area. He knew that there was a Menlove Avenue quite well, and the Gardens apparently being off of the Avenue according to fellow club members, he surely felt confident it would be quite trivial to find.

Menlove Avenue is a rather well known road in the Mossley Hill area, running alongside Calderstone’s Park which William occasionally visited with Julia “to see the roses”. Menlove Gardens is a triangle of three residential streets, those being Menlove Gardens North, South and West respectively. Considering that many new streets were being built around that time and people of the 1930’s lacked the luxury of Google Maps, one might be fooled into thinking Menlove Gardens East was a new street which would be somewhere in the general vicinity of Menlove Avenue/Menlove Gardens.

Here’s the kicker: There isn’t (and still isn’t) any such place as Menlove Gardens East, and there was no R. M. Qualtrough. Whoever had placed the call was apparently sending Wallace on an impossible journey to meet a man who doesn’t exist at an address that doesn’t exist.

At about 22:15 William leaves the club and is noticeably delighted at having won his game against Mr. McCartney, enthusiastically talking his friend James Caird through the finishing moves. Before they part company, he brings up the name “Qualtrough” and what a peculiar name it is. Caird responds that he has only ever heard of one man by that name. Afterwards the pair briefly discuss the best route to get to Menlove Gardens. Wallace tells Caird that he may not even go but rejects his route suggestion, instead opting to “take the more direct route” into town and then out from there to Menlove Avenue. They go their separate ways, with Wallace arriving home at around 22:55 where his wife had supper prepared for him. They retired to bed around midnight which was their custom.

Unfortunately Julia is not her usual self tonight. Her beloved black cat “Puss” is missing and she’s beginning to worry. Although Puss was not originally Julia’s cat, while catsitting for vacationing neighbours, the two struck up such a bond that when the neighbours returned they decided Julia should keep it.

As concerned as Julia probably was that her dear cat had vanished in the bitter cold of the January winter, it surely never occurred to her that it was herself who now had less than twenty four hours to live.

THE DAY OF THE MURDER (20th January, 1931):

The next day at 10:30 AM William leaves his home to begin his collection rounds wearing a dark slate grey raincoat (a mackintosh) to shield himself from the poor weather, collecting insurance money which he will later place into a cash box that will play a central role in this mystery. He returns home at 14:10 to have lunch, hanging up his rain-soaked mackintosh in the hall near the front door to dry. The rack was directly opposite the door to the parlour, and had once also held a “dog whip” which Wallace said he had not seen for some 12 months. He would similar claim for there to have been a small wood chopper in the kitchen which had not been seen by him for the same length of time, which was discovered by a Policeman (Herbert Gold) in a basket under the stairs, beneath a pile of clothes.

At 15:15 William dons his lighter fawn raincoat, apparently owing to the weather having turned out for the better, and goes on his afternoon collection rounds. Just 15 minutes later at 15:30, a police constable named James Edward Rothwell who knew Wallace as an insurance agent was cycling down Maiden Lane. In a statement he would make after the murder, he said that he passed by close to William (who was looking down at the ground and did not notice him), and saw that his face appeared “haggard, drawn, and unusually distressed”. He went on to say that Wallace dabbed his eyes with the sleeve of his jacket and it gave him the impression he had suffered some sort of bereavement…

Very shortly after this sighting William called on a client who in court testified that he was his usual self and was joking with her. During the trial, the defence called a number of client’s William had seen shortly after this time as witnesses. All reported that he seemed his usual self and nothing was out of the ordinary in his manner whatsoever. One had even offered him a cup of tea which he gratefully accepted before returning home. All reported that they found Wallace to be a very pleasant man indeed.

In court the defence attempted to convince the constable that he was mistaken by using the existence of these witnesses, and by explaining that William may have been dabbing his eyes due to the cold weather. But the constable remained firm. Although he admitted eyes may water in such cold weather, in spite of that, and in spite of any witnesses the defence could call to testify they found Wallace to be completely normal – even jolly – just minutes after this sighting, he was unprepared to change his opinion.At the same time as this sighting (15:30), Amy Wallace arrived at 29 Wolverton Street to visit Julia (her last visit being with her son Edwin the Sunday just gone). Amy Wallace was William’s sister-in-law, married to William’s younger brother Joseph Edwin Wallace who worked abroad in British Malaya. According to Amy Wallace, during the visit she found out from Julia that William was heading off to a business appointment somewhere in the Calderstone’s district that night, and that she and Julia had discussed a spate of recent burglaries in the living kitchen of the Wallace home.

At some point during this visit the baker’s boy Neil Norbury arrived to deliver Julia’s bread. Expressing concern for her health since she did not look at all well to him (he would later describe how she had a scarf or “bit of material” around her neck), Julia reassured him that it was just a touch of bronchitis – nothing serious. By this point she had been stricken with illness for around two weeks.

Amy said she left Wolverton Street at around 16:30 having invited Julia to a pantomime she had tickets to, and it was around this time that window cleaner Charles Bliss scaled the yard wall from the back alleyway and began working on the back windows of 29 Wolverton Street. Julia went out into the yard and paid him a shilling of which she received three pence change.

By 17:45 William was just finishing up his last insurance round for the day, returning home by what he estimates to be 18:05, and eating an evening meal consisting of scones with Julia. This meal he says was finished at around 18:30, and the fact it took place is corroborated by the later autopsy. It is just before his arrival home at 18:00 when it could be expected the milk would arrive, either from Allan Close or, if he was running late, possibly be Elsie Wright his coworker who had delivered to and seen Mrs. Wallace the previous night the 19th. Mrs. Johnston said the boy had often been late recently and the milk could come any time between 18:00 to 19:00.

Between 18:25 and 18:35 a local paperboy David Jones pushes the day’s issue of the Liverpool Echo through the letterbox of 29 Wolverton Street. This newspaper would later be found on the table in the living kitchen. [According to Goodman it was open at its center pages although corroboration of this is something I have been unable to find]. He did not see anybody else about the street, nor did he hear any sounds/commotion or see any lights in the Wallace home – including coming from the front parlour where the murder took place.

Just a touch after 18:35 at what is likely to be around 18:39, Julia would reportedly be seen alive by a witness other than Wallace for the final time. Many authors give the time as earlier than this, and I would gladly do so to seem “fair”, but the fact of the matter is that all testimony seems to support a later time. More on this can be seen here: Allan Close statements as well as here… The important factor to me it the paper delivered by Wildman who claims he is sure he got into Wolverton Street (through an entry emerging beside #21) at 18:37 to 18:38. He delivers several papers in this street including to Walter Holme, Wallace’s neighbours at #27.

According to Holme, he heard Julia shut the door of Wolverton Street at what he guesses is 18:35, since it is 5 minutes before he received the paper. This is quite impossible, since his paper delivery boy is Wildman, and Wildman had delivered the paper and left #27 with Allan Close still standing at the doorstep of #29 in his Shaw Street School cap as he (Wildman) departed – presumably to begin deliveries on the opposite side of the road where he delivered to four even numbered homes before going down an entry into Redford Street. He did not hear or see the milk boy speaking to anyone, implying that Julia had not yet returned to the door or closed it when Wildman left the doorstep of #27 to begin his deliveries on the opposite side of the road [the presumed route he would take, given he emerged on the “Odds” side of the street and all other deliveries were “Evens”].

This critical milk boy witness is 14 year old Allan (often spelled by others as Alan) Croxtorn Close, and he would testify that he had knocked on the front door of 29 Wolverton Street “between 18:30 and 18:45”, leaving the milk jugs on the doorstep, before going next door to deliver milk there at the Johnston’s home where the front door was already open. He left the jugs in the lobby and closed the door of #31, the door of 29 Wolverton Street opened and the milk jugs were taken in. Alan Close then returned to the doorstep of 29 Wolverton Street to collect the empty milk jugs which were given back to him some minutes after by an alive Julia Wallace upon her return to the door… They discussed their respective illnesses briefly, with Julia urging Alan to hurry off home out of the cold. The front door of the Wallace household then shut for the final known time.

I do believe the most plausible time for the door closing is 18:40 given the statement of Wildman previously mentioned. Elsie Wright seems to have also been in the street at this time with Allan, likely so that he would accompany her through the dark unlit entries which he did the following day. She did not mention this in her own statements, but Wildman seems to have seen her standing in the street waiting for Allan.

Allan, Wildman, and also David Jones who delivered the Echo to the Wallace house reported seeing no lights in the front room of 29 Wolverton Street, although Allan who could see right through the house owing to the wide open front door did see a light on in the middle kitchen where the Wallaces had just finished eating shortly prior.

It’s roughly during this period, during the arrival of the paperboy and milk boy that Wallace is busy preparing himself for his business trip. He changes in the upstairs bedroom, combs his hair in the upstairs bathroom, and gathers documents together which he may need for what he assumes is likely some type of “coming of age” endowment policy for “Qualtrough’s” girl’s 21st birthday. He can expect a very handsome commission off of such a policy if he can secure the deal, and having gone unrecognized and unpromoted after 16 years of loyal work for the Prudential he must have felt very proud to finally be noticed for his impeccable work. In all the years he worked for the Pru his books had always been in perfect order.

According to Wallace, it was Julia who had convinced him to go on the trip since he himself was unsure. After all – while reasonably financially comfortable as far as anyone can tell, who are they to turn their nose up at the potential of a handsome commission?

William then sets out on his journey to Menlove Gardens East at around 18:45, wearing the lighter fawn jacket he had worn earlier on his final rounds of the day when seen by P.C. Rothwell and various Prudential clients. The next time anyone sees Wallace’s darker mackintosh it will be considerably burnt and lying in a pool of blood beneath his wife’s dead body. Wallace claims that Julia followed him down the yard bolting the gate behind him (though he did not hear the bolt being drawn), which was their usual practice when one of them was going out owing to the convenience of this route for reaching the tram stops quicker. With the trams he states to have taken, the latest he could have left the house to make this journey would have been in the region of 18:49.

Police tests seem to suggest about a 16 to 20 minute time to the second tram stop (it was the second tram William boarded where he was first noticed), with the trams coming at roughly 6 minute intervals… Wallace stated that upon his arrival to the tram stop, he had to wait 3 to 4 minutes for a tram, which would make his claim of 18:45 essentially spot on accurate within a minute or two. Wallace was quite a time-conscious man in the habit of checking the clock and his wristwatch at regular intervals according to one client, so regarding the accuracy of times he would be quite a strong witness unless one was of the opinion he is guilty and lying.

In regards to the tram tests conducted by the police, it is known that in some reconstructions officers had jumped onto moving trams at the wrong stop (a request stop at the top of Castlewood Road) or sprinted the final leg to catch it (which on the surface seemed quite unlikely for the sickly Wallace – especially to do so without being remembered at all and being possibly out of breath from battering his wife to death). The existence of the request stop is significant: If Wallace wished to make his appointment on time and wanted to be noticed, it seems it would have been a good choice to use the request stop which would require flagging down a tram, increasing the likelihood of being noticed in an inconspicuous manner. One of the points against the man is that he arrived to Menlove Gardens West with only 10 minutes to spare. The time allowed to himself upon arrival could have potentially been greater had he used the request stop.

According to locals who gave character reports on both William and Julia, William was in the habit of walking long distances to save money on tram fares. In conjunction with petty arguments recorded in his diary around three years earlier about Julia having purchased too many newspapers, and Julia keeping money hidden in her corsets, one can assume Wallace was quite a miserly man – only “splashing the cash” when it came to his hobbies. His wife suffered the consequences of which it would seem, wearing mostly homemade clothes, although she seemed to greatly enjoy needlework and had an artistic bent: Many of the paintings in the Wallace parlour are her own work, and Wallace had described her as “no mean artist in water-colour”. Much of her work can be seen in the parlour:

But in any case Wallace stated he left his home at 18.45, and on the surface of things, it seems to be a very accurate estimation on his part.

The Tram Journey

Double decker trams like this were a common form of transport in 1930s Liverpool. Typically two conductors would work on these trams, most often taking tickets when passengers boarded. Because cars were so unusual, public transport, walking, or cycling were the most common forms of transport at the time.

The first time Wallace is seen (or at least remembered) by anyone after leaving his home is on the second tram (Smithdown Lane) at 18:06. Wallace inquires of the conductor Thomas Charles Phillips if this tram car goes to Menlove Gardens East. Phillips informs him that while this particular car doesn’t, he can instead take a No.5, 5A, 5W, or No.7 car… But Phillips quickly changes his mind, telling Wallace that he can get on this tram car and that he will give him a penny ticket for a transfer.

Wallace boards the tram telling the conductor that he has an important business call to make and wants Menlove Gardens East, saying he is a “stranger in the district”. He repeated his need for this address when the conductor punched his penny ticket: “You won’t forget mister, I want Menlove Gardens East.”

Shortly after, when the conductor returned downstairs having seen to the upstairs passengers, Wallace spoke to him again asking “how far is it now, and where do I have to change?” The conductor informed him that he would need to change at Penny Lane, and for Wallace’s benefit when the car arrived he exclaimed “Menlove Gardens, change here!” At this announcement Wallace alighted from the tram while Mr. Phillips told him to hurry for the No.7 tram in the loop. Phillips then spotted a No.5 tram and stated, “either that one (the No.5) or the other one in the loop.”

From the next sighting we can gather that Wallace boarded a 5A tram, asking the conductor of this tram (Arthur Thompson) to put him off at Menlove Gardens East. Upon arriving at Menlove Gardens West the conductor informed him: “This is Menlove Gardens West. Menlove Gardens is a triangular affair, three roads. There are two roundabouts off on the right. You will probably find it is one of them.” William thanked the conductor, adding that he “is a complete stranger round here” before alighting.

The Hunt for Menlove Gardens East

Having arrived at Menlove Gardens West at around 19:20 (10 minutes until his scheduled appointment with Mr. Qualtrough), Wallace begins his quest to find the mythical Menlove Gardens East. He began by walking down Menlove Gardens West into Menlove Gardens North, where he encountered a woman leaving one of the homes which was, he said, about the seventh or eighth house down (18 or 20 Menlove Gardens North). He asked her if she could direct him to Menlove Gardens East, but unfortunately she said she “does not know where it is but that it might be further up in continuation of Menlove Gardens West.”He then walked back down Menlove Gardens West as per her suggestion until he reached a road to his right – Dudlow Gardens. Retracing his steps, he arrived back at the junction of Dudlow Lane and the top of the lower part of Menlove Gardens West. Here, Wallace approached a young, very tall fair-hared man named Sidney Hubert Green. Such a towering man must Sidney Green have been, that he mistook the 6’2 Wallace as a mere 5’10.

He asked Green (who remembered Wallace as 5’10 and thin, wearing a darkish overcoat and trilby hat) if he knew where Menlove Gardens East was. In one of the more prolonged of the conversations he had with strangers that night, Green told him that Menlove Gardens East does not exist, but that there is a Menlove Gardens West. William informed Green that he knew that and then went to knock on the door of 25 Menlove Gardens West, apparently suspicious Beattie may have copied down the address wrong. Green seems to have largely forgotten the details of the conversation by the time he was questioned, believing it was 24 or 26 Menlove Gardens East Wallace had requested.

Katie Mather of 25 Menlove Gardens West answered Wallace’s knock and was asked by Wallace if this was Menlove Gardens East, and if Mr Qualtrough was there. Katie Mather responded in the negative. She remembers listening “The Geisha” on the wireless programme which began at 7 PM, but wasn’t sure if Wallace had called at her house before or after she had started listening to this.

Having hit another dead end Wallace decided to try Menlove Gardens South and North, but immediately discovered they only had even numbers (and therefore could not have a number 25), before walking to the end of Menlove Gardens North which led out onto Menlove Avenue. After asking another stranger waiting at a bus stop where the address is with no luck – the man also being a stranger in the area – and finding himself at the top of Green Lane, William decided to call at his supervisor Mr. Joseph Crewe’s home which was further down this particular road, a place he had visited on a number of occasions.

(Curiously, Dr. MacFall who would later give forensic testimony at the trial also lived on this street, and one wonders if he and Crewe knew each other and neighbours, and if so, what conversations may have taken place between the men!)

Wallace knocked on Crewe’s door, but unknown to him at the time Crewe had gone out to the cinema, and so he was met with no answer.

Finding that Crewe was not home and with hope dwindling, William trudged down Green Lane and came across James Edward Serjeant at around 19:43, an officer on the beat in the area who had just left Allerton Police Station. He asked the officer if he could direct him to where Menlove Gardens East was, to which the officer informed him that no such place exists – that there is a North, South, and West, but no East. William said he had tried 25 Menlove Gardens West already and the man he wants does not live there… Wallace, claiming that the man was of the “friendly type”, explained to him his dilemna and all about the telephone message he had received. The officer suggested trying 25 Menlove Avenue in an attempt to be helpful.

As Wallace went to turn away, he turned back and asked the officer if he knew where he could find a street directory (which at the time was much like a modern day phone book). The officer suggested he might find one at the local police station or Post Office, at which point William checked his watch, saying to the officer: “It is not 8 o’clock yet.” the officer did the same and confirmed that it was indeed a quarter to 8. Based on an average walking pace, Wallace would have arrived at the Post Office two minutes later at 19:47. Wallace said that his reason for checking his watch was not to impart the time upon the officer (a time which would, in fact, be quite useless to establish compared to other more critical times), but because he believed the Post Office may close at 8 PM.

Unfortunately there was no directory at the Post Office, but Wallace asked the clerk there if they knew of a Menlove Gardens East or Qualtrough. They said they did not but advised he try the newspaper shop. William noted the time on the clock of the Post Office (noting that it was now 19:54), then went a little further up the road to the newspaper shop where he found a directory.

When the newspaper shop manageress Lily Pinches approached him to see if she could be of any assistance, Wallace apparently requested help finding the address. Her testimony is very poor so it is difficult to know what exactly was said… For example she claims that Wallace had said the name Qualtrough to her, then that he didn’t, then that he did, then that he didn’t and she swears he didn’t. She also states that he came into the newsagents at 20.10, when Wallace states he had caught the tram home at 20.00 (albeit based on the time he spent in the Post Office and the time he left it, as well as the time he got home, it would seem more likely he caught the tram after 20.00)… But what we do know is that this inquiry was a fruitless one, and it was apparently at this point Wallace gave up his search. Given a recent spate of burglaries which the Press stated had left several neighbours in the street nervous, Wallace claims he felt “uneasy” about the whole thing.

Recognizing where he was and being familiar with this route from Allerton, having taken this particular route to and from Mr. Crewe’s house was situated closer to Allerton Road than to Menlove Avenue, Wallace hopped on a tram and mostly followed the same route home, except going to his front door first instead which was his practice late at night. No tram drivers on his journey home came forward to testify that they had seen him, nor did any passengers on the trams.

The Discovery of the Body

Though Wallace stated that he never spoke to anybody on the way home, a local typist named Lily Hall who knew Julia from church and had known Mr. Wallace by sight for years gave a statement not too long after the murder which contradicted this. Apparently she saw Wallace standing opposite the back entry of Wolverton Street (at a little entry on the opposite side of the road beside the local parish church) in a darkish overcoat and trilby hat talking to another figure, who she described as 5’8 and of stocky build, wearing a dark overcoat and cap. However William denied this – stating that he did not speak to a single soul on his journey home apart from the tram drivers from whom he must have purchased a ticket.

Her statement is a little confusing and muddled, and she gave several testimonies which can be seen here with a detailed analysis.

In any case, it’s at around 20:40 at night when William tries his key in the front door but finds it will not open (after finally entering the home and later admitting a police officer, he said he found the door was bolted from the inside). How strange! He knocked gently but received no answer. Of note, the Holmes family at #27 whose front door was directly beside Wallace’s did not hear these knocks – but it is likely they happened since the knocks at the back door of his home were corroborated by Florence Sarah Johnston of #31 Wolverton Street.

He went round to the back finding the yard gate closed but not bolted, and went up to the back door. He attempted to open it but felt as though it was fastened against him. Knocking gently on the back door he again received no answer (his neighbour Florence Johnston heard this knocking as mentioned – his “usual knock” she said). He then went round to the front door to give it one more try… Once again he could not get in and there was no response from inside the house. At this point he began to feel some level of concern and hurried round to the back for the second time where he had a chance encounter with neighbours John Sharpe Johnston and Florence Sarah Johnston, who said they were just headed out to visit a local relative of theirs named Phyllis.

A slightly anxious William asks them if they’d heard anything unusual tonight. “Why, what’s happened?” Florence asked. Wallace tells them he’s unable to get into his home after trying both doors, so John tells him to try to open it one more time, and if he can’t, he’ll go and get his own key and try. “She won’t be out, she has such a terrible cold…” William muttered, seemingly having briefly considered the innocent explanation she had gone out to post a letter which she sometimes did.

When Wallace tries the door again in the neighbour’s presence it opens easily, which William signals by calling out “it opens now”. William claims that it was HE who asked his neighbours to wait outside while he checked around the house, although according to the Johnstons in an amended statement it was John who suggested they wait outside as he goes and looks around to ensure everything is well. Wallace stuck to his own story even though he was aware the Johnstons had changed theirs (which Moore was furious about and brought up in a formal police report).They carefully watch his passage through the home by the lights and matches and John (who is partly deaf in his right ear) hears him call out “Julia?” twice inquisitively as he heads upstairs into the middle bedroom where the couple slept, apparently believing his wife may have gone to bed ill. Eventually he strikes a match in the dooway of the the dark parlour downstairs (which had the door ajar but not shut) and finds his wife on the floor. He claims to have believed she may have been in a fit and crossed to light the gas jet to the right of the firplace, which was the usual gas jet they used. To his horror he sees her skull smashed open with blood and brain matter oozing out, and blood sprayed up the walls. He hurries outside and in an anxious tone tells the Johnstons: “Come and see! She’s been killed!”

“What’s wrong? Has she fallen down the stairs?” Mr. Johnston asks. Following William inside they come across the gruesome sight of Julia’s lifeless body in the parlour. Though no furniture has been displaced, blood has been sprayed as high as 7 feet off the floor, spattering the walls, furniture, and various phorographs and Julia’s framed paintings, with visible brain matter which has oozed out of a large open wound in her skull. The wall above the piano had also received some of the blood spatter. A large pool of blood has collected under Julia’s body with two other blood pools in a circle round to the front of the easy chair to the left of the fireplace upon which rested Wallace’s violin case. According to Wallace he had last played violin in the kitchen on the 19th, unaccompanied by his wife who was presumably too unwell to wish to play piano, but it was the general practice of the couple of play music together “every evening”. Wallace’s nephew Edwin claimed that on Sunday (the night before the Chess Club and phone call) the couple had played music for them, but Wallace disagreed. The Johnston’s had not reported hearing music in the days leading up to the murder, according to Russel Johnston – grandson of John and Florence Johnston and son of Sarah and Robert Johnston – which corroborates William’s version of events.

“Oh you poor darling.” says Florence Johnston. “Is she cold?” asks Mr. Johnston, to which Florence shakes her head in the negative. William continues to repeat “they’ve finished her… They’ve finished her”, and adding at some point “look at the brains.” Wallace requested that John Johnston go for a doctor although he added he “didn’t think it would be much use”. “Any particular doctor” remarked Mr. Johnston, to which Wallace replied “the nearest one!”. After this the three of them lurched back into the living kitchen away from the grisly sight of the poor battered woman.

According to William the parlour was only used for entertaining guests or musical evenings he shared with Julia, where she would play the piano while he accompanied her on the violin. Friends and relatives aside from just Edwin and Amy Wallace were often treated to these musical events (many probably hiding a grimace behind a fake smile as Wallace screeched out notes on the violin to the tune of his wife’s masterful piano accompaniment). There was a chaise lounge in the bay window which Julia, according to Gordon Parry many years later, would recline upon when entertaining guests.

While in the living kitchen (back in those days the “living kitchen” was the equivalent of the living room), William pointed the Johnstons in the direction of a cabinet lid (described by Moore as a “flap door” which had evidently been previously broken and shoddily mended) was on the floor broken in two: “Here’s a cabinet door they’ve wrenched off”. On the floor were a small number of coins: a half crown and two separate shillings. “Is anything missing?” asked Mr. Johnston. William then reached up and took down his insurance collection box from the top shelf of a bookcase (7’2″ off the ground), and noted that it had been looted. All that was left was a single dollar bill and four stamps. Wallace replied that about £4 was missing (which was apparently made up of a mixture of notes and coinage), but that he couldn’t be sure until he’d checked his books.Mr. Johnston urged William to go upstairs once more and check everything is in order before he goes for the police. William went upstairs returning not long after, saying that everything was in order and that there were five pounds in a dish that they hadn’t taken (it was £4 in pound notes, along with a postal order for 2/4, and a half crown. Wallace would later say he probably miscounted them). With this, Mr. Johnston went for a doctor and then to the police.

As Mr. Johnston went for the police he coincidentally bumped into his daughter Norah’s fiancé Francis George McElroy close to the house, who had been on his way to see their daughter Norah who was still in #31. According to Russel Johnston at some point later his father (Robert Johnston) having returned from work and being informed by his wife Sarah Johnston (also both living at #31) that his parents were next door at the Wallaces. He had entered the Wallace home during this time and found Florence in the middle kitchen, with Wallace in the back kitchen cutting up meat for Julia’s cat “Puss”, which had returned shortly after the arrival of the police. This was seen as rather callous. According to Florence it was actually John who had witnessed this.

Regarding the cat, MacFall also believed that William’s stroking of the cat seemed to him rather callous, although a later letter sent to Goodman after publication of his book “The Killing of Julia Wallace”, described how when Wallace had visited them after his successful appeal, he had almost instinctively bent down to stroke their cat as it walked past. Obviously a “compulsive cat-stroker” the writer had mused.

William and Florence then returned to the parlour again, still alone in the house at this point, where Florence again felt Julia and noticed that she had cooled down since she last checked. “Whatever have they used (to kill her with)?” Florence asked, while glancing around the room. In court this line was falsely attributed as being said by William, and was used against him by the prosecution. Wallace himself seemed to have been quickly tricked into thinking he actually said it, defending it as a “natural thing to say”. Florence stated that in response to this remark, William had patted around under the edge of the hearthrug as though feeling for a possible implement of murder.

As Florence and William examined the body closely William, crossing from the window side of the room, stooped down fingering a piece of material stating: “Why, whatever was she doing with her mackintosh – and my mackintosh?” “Why, is it your mackintosh?” asked Mrs. Johnston. William confirmed that it was. Florence herself claims she had stayed on the sideboard side of the room and had not crossed the room at all. Wallace would immediately confirm it again to officer Williams (the first officer to arrive at the scene a little later) who noticed and inquired about it, and Sergeant Breslin – although later when asked yet again he would hesitate considerably, before finally saying “if there are two patches on the inside it is mine.” This hesitation in identifying the jacket would also be used as evidence against him. The detectives who noted his hesitation did not know he had already identified it on three occasions.

Florence and William return to the kitchen. Not knowing what to do in the situation, Florence exclaims they will have a fire, and begins to stoke the kitchen fireplace which Wallace eventually begins to help with. According to Florence, Wallace put his head in his hands and cried twice in her presence, but when the police arrived he made a great effort to pull himself together. John Sharpe Johnston would describe Wallace as a man who appeared to be in shock.

The Original Body Positioning: Julia was lying on her right-hand side, almost diagonally across the rug, her legs slightly parted, her feet lying flat on their sides close to the right-hand end of the fender, toes pointing toward the window. Her right arm was hidden beneath her body; her left arm lying against her body, was bent at the elbow, the forearm resting over her chest, the fingers almost touching the floor. Approximately 18 inches from the open door, Julia’s head lay on its right side, her eyes staring out toward the window. Surrounding her head was a 9-inch border of congealing blood, brain tissue and bone. Just above, and in front of her left ear was a huge, cruel opening in her skull, 2 inches wide by 3 inches long, through which what remained of her brain could be seen.

According to Florence, the VIOLIN STAND was directly behind Julia’s head, NOT the chair upon which there is music. This is significant and makes more sense, as Julia would likely keep a chair in front of the piano, while the violin stand would be kept beside the piano where William could play alongside his wife.

Frankly in this case, the efforts of the photographer were seemingly pathetic to a level which defies comprehension, him having only bothered to photograph the kitchen after almost all evidence including the handbag, broken cabinet, coins, and cash box (although many publications claim it is that circled box up top?!) were seized on the 21st of January. Also of significance, William had stayed ALONE in the house on the night of the 21st, before the photograph was taken.

The Police Arrive

The first policeman to arrive at the scene is a PC Williams. Constable Williams follows Wallace around the home. Finding the laboratory in order they go into the bathroom where there is a light on. “We usually have a light on in here” Wallace says. They then go into the middle bedroom where the Wallaces slept, and the gas light in this room is also burning. Constable Williams questions this, to which Wallace explains that he changed himself in this room and that he himself had probably left the light on. He then goes to an emptied out jam pot on the mantlepiece and partially extracts the pound notes (later one was found to have blood smeared across it): “Here is some money which has not been touched” Wallace says. Constable Williams immediately tells him to put it back where he found it, and Wallace complies.In the front bedroom the Wallaces used as a spare room there was no light, but the bedsheets were partially off and the pillows on the floor, though nothing had been taken according to Wallace (who found items such as his wife’s jewelry still in the drawers), and all drawers were shut. Wallace said he had not been into the room in about two weeks and therefore could not say whether or not it was like that when he left.

After inspecting the kitchen – with Wallace reporting the money looted from the cash box, and apparently something about the money in Julia’s handbag which the constable could not make out (nothing had been taken from it), they went back to the parlour.

The constable asked Wallace if any lights were on in the house when he returned. He explained that apart from the two upstairs (in the bathroom and middle bedroom), the home had been in darkness.

Many other police officers, doctors, and forensics would soon arrive at the scene. “Julia would have gone mad if she had seen all this” Wallace remarked, referring to what he felt would be his wife’s reaction to so many strangers milling around the home… Unfortunately the attending officers did a very poor job in preserving the crime scene. In fact, one detective who turned up drunk actually went upstairs and flushed the toilet. This was the same toilet on which a blood clot was found, meaning he may well have flushed away vital evidence! Another mistake was made: The police had foolishly emptied the milk to feed the cat who was left in the house as they continued their investigations. Milk which could have provided vital clues: E.g. to prove the milk HAD in fact been taken in, and also to note whether or not it had been emptied into the cat’s dish.

The Police Theory

William: “Try getting a reservation at Cottle’s City Café now you stupid *expletive*! (Pictured: Patrick Bateman in the infamous “American Psycho”).

The police who were already working on the assumption that the husband is almost always the killer could not quite believe their luck. Surely it was Wallace himself who made the call in an attempt to provide himself with a bulletproof alibi! In fact according to Moore, the police were sure Wallace was guilty on the VERY NIGHT OF THE MURDER, but having found no blood upon him did not have enough evidence to detain him.

As the police frantically worked on this theory, a spanner was thrown in the works when Alan Close came forward to attest to the fact that he had seen Julia Wallace alive when he delivered the milk to the house at 18.45 on the day of the murder. Others in the neighbourhood had seen Alan Close. One significant witness who was making a delivery to 27 Wolverton Street (to Walter Holme, proving Holme’s statement false) remembers seeing Alan Close right next to him (wearing a collegiate cap) on the doorstep of 29 where the Wallaces lived at what he said would have been shortly after 18:37 or 18:38, the time he would have arrived in Wolverton Street before walking 5 doors up to #27. When he left #27, Allan Close was still standing at the doorstep with the door wide open. He did not notice any light in the Wallace’s front room at this time, and noticed what sounds like Elsie Wright standing nearby holding some cans.

The police now had a serious problem… How could Wallace have murdered his wife, cleaned himself of blood, and left the house within a matter of minutes?! Through tests in which Alan Close was made to cover the distance of his route (500 yards) while stopping off to make deliveries, drop off empty milk jugs at his dairy and pick up a new full crate to carry around, the police managed to convince Alan he was wrong about the time… By their tests they convinced Alan Close that it had actually been 18:30 when he had last seen Julia… Even though this contradicted literally every single witness testimony. The closest was Florence Johnston who claimed to retrieve her milk at “about 18:30”, but we know the door closed on her before Allan returned to the open doorstep of #29, and before Julia had a short conversation with Allan and closed the door on him.

Allan’s own watch which he checked in Redford Street also appears to contradict the apparent “18:30” timing. In a rather ludicrous case of suppressing evidence, the prosecution objected to the appearance of several witnesses who could have proved Allan had delivered the milk later than the claimed 18:30.

Even still with the false 18:30 time, the timing was tight to have done what they suggested: Killed his wife, staged a robbery, then went upstairs to clean himself in the bathroom, before then leaving his back door and catching the tram. The officers set about testing the tram route, with the officers jumping onto a moving tram in one of these reconstructions, or sprinting to head off a tram which was just about to depart, sometimes using a closer “request” stop which William did not even claim to have used. Through these tests (but also, fairly, the tests of P. Julian Maddock hired by the defence), it seems William could absolutely not have left his back door later than 18:49 to have made the tram – even hurrying at a fast pace. William claimed a wait time at the first tram of 3 to 4 minutes, corroborating his claim of 18:45. Since the door most likely closed on Allan at 18:39 or 18:40 if we analyze the witness testimony, Wallace had at most 9 or 10 minutes to lure his wife into the parlour, batter her to death with multiple blows, stamp out a fire, and leave the back door. But given the more likely leaving time of 18:45 (the average tram wait was 6 minutes, to make the 18:49 leaving time accurate he would have had to have gotten lucky and jumped on a waiting tram), we are really talking 5 or 6 minutes.

Even if we assume he did not need to wash himself, and had staged the robbery in advanced or on his return to the house, this is still stretching plausibility.

Adding to this Wallace was a sickly man just recovering from a bout of flu at that (“the winter months tried Mr. and Mrs. Wallace” Florence Johnston would state)… Those who knew him said that he moved quite slowly, probably owing to his single kidney and the kidney disease which had plagued his entire life. Besides that Wallace was a tall and extremely distinctive figure, dressed in what would be considered eccentric (outdated) clothing even for the 1930s. Certainly nobody recalled seeing a very tall skinny figure jogging through the alleyways of Liverpool in Victorian-style getup, nor did conductors seem to recall such a man leaping onto or heading off their tram… And another blow came when the captain of the chess club who had known wallace for 8 years, Samuel Beattie, attested that, even KNOWING the assertion that Wallace made the call to himself in a disguised voice, and asked to consider if it was his voice, he replied that “it would take a great stretch of the imagination” to say that the voice (which made the Qualtrough call) was anything like Wallace’s.

Wallace found himself stuck in a position of trying to prove he did not make a telephone call which, apparently, he did not make.

While recounting the voice to Roger Wilkes years later, Lillian Martha Kelly would say:

“Later of course I heard Wallace speak at the trial, but I could not have sworn it was the same man.”

To make matters worse, when drains, basins, and toilets (etc.) from the home were inspected, no blood could be found – and the towels were all entirely dry with no sign of having been recently used… The highly sensitive benzidine test was applied to the clothing William was wearing that night in an attempt to uncover hidden bloodstains, but none were found.

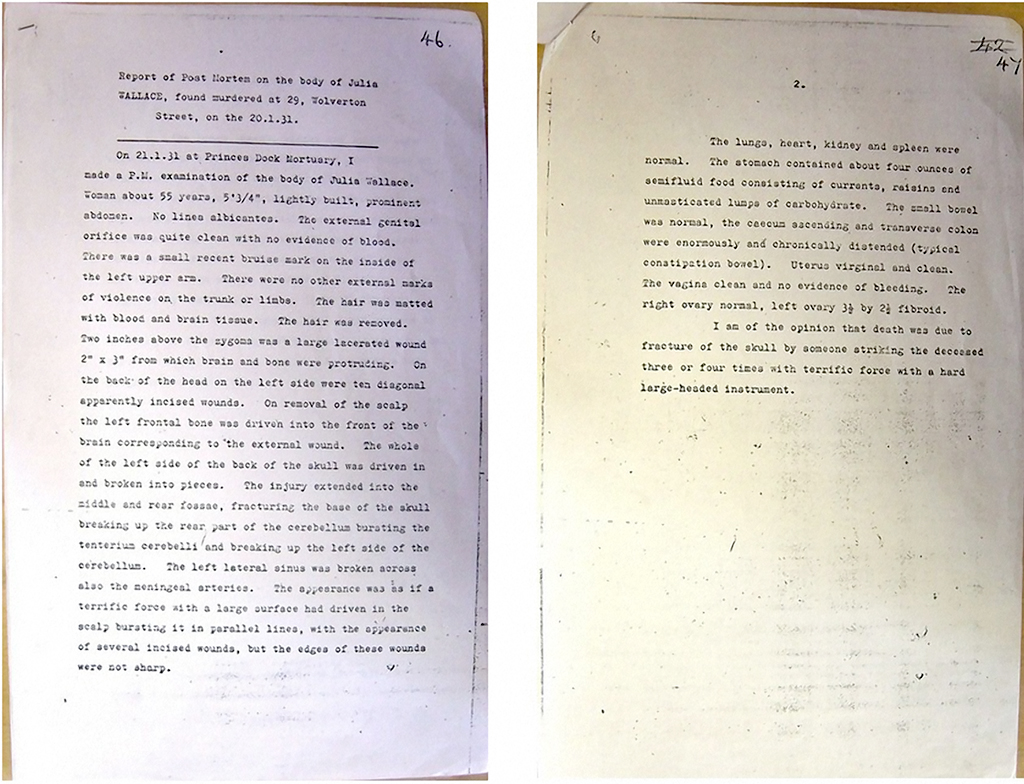

The initial forensic report by McFall which you will find below would also have damaged the case, as the time of death is placed at 19:50 (with 3 or 4 reported blows) when Wallace is known to have been miles away from home. This is vastly different to the 18:00 time and 11 to 12 blows McFall would claim at court. Although the time of death can only be supplied as a window by forensics, even in modern times with the most modern techniques available, we will see below:

The post mortem report by McFall. This report puts her time of death at 19:50, with only 3 or 4 total strikes. Significantly different from his later reports which give a time of 18:00 with 11 to 12 blows.

And so an idea was quickly formed that the reason Wallace was able to leave on his journey for Menlove Gardens without a trace of blood upon him, and so soon after his wife was last seen alive, was because he had worn the mackintosh as a shield to protect himself from blood splatter.

Indeed… The final police theory was this: On the 19th of January, Wallace placed a telephone call to himself from a payphone just a couple of minutes from his house using a disguised voice to talk to the familiar Samuel Beattie. He then went to the chess club to receive this message, faking cluelessness as the details of his very own message were given back to him.

Then the following night, Wallace patiently waited for the milk boy Allan Close to arrive and provide a timestamp of when Julia could be verified as last being alive, then lured her into the parlour with a pretense that he wanted her to set up the room for a musical evening (evidently telling her he’d given up on the idea of the trip), before donning the mackintosh nude and bashing her to death with either an iron bar or poker, two items which the charwoman had reported were missing from the house.

The fact he is proposed to have been nude, by the way, would have necessitated dressing himself afterwards adding to the time it would take to leave the house. We can ascertain that if it caught light while he was wearing the jacket the clothing underneath would have been charred. And if he was “holding it up” as a shield, it seems like an act of insanity to have grabbed his very own jacket to use as a shield.

(The idea that Alan had actually seen Julia was not really believed by forensic expert McFall or the prosecution, who rather believed Wallace had dressed as his wife and put on a false accent to trick Alan).

Very quickly, they claim, Wallace attempted to burn the jacket but aborted the idea (possibly due to the smoke and scent?), chucked it on the ground, and pulled his wife’s body on top of it where he then beat her on the back of the head a further 11 or 12 times. After this, he put on his other jacket, cleverly hid the iron bar up the sleeve (prosecutor Mr. Hemmerde would provide this theory to someone who had asked him about the case some time after the trial and appeal), and made a dash for the tram.

It was asserted that he had found a clever place to hide the bar at some stage on his trip, although the Cleaning Department was tasked with searching all street grids in the neighbourhood and found nothing. He apparently then set about implanting into people’s minds the idea that he was out at specific times (despite only actually mentioning one inconsequential time to a witness: 7.45 PM), to build the alibi he had expertly crafted for himself. Indeed, he spoke to many people on his trip, from conductors, to shop workers, to pedestrians, to police officers, and it was the theory of the police that he did this in order to show he was not at the house when the crime was committed… Though being strangers, it was really only luck that they were traced or came forward (the witness at the bus shelter did not).

Murderer Scot-Free?

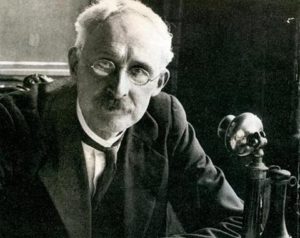

Richard Gordon Parry as he appeared on a poster for a drama production a year before the murder. For many years before the release of the case files he was slated as the murderer of Julia Wallace.

Wallace himself claimed that he knew exactly who the killer was, and fingered Richard “Gordon” Parry as the man who had murdered his wife in the last of the articles for John Bull magazine (though Parry’s name is not given). In Wallace’s second statement to police in which he gave the names of men his wife would admit without question, Gordon’s name was first, followed by a large amount of detail.

Following the name of Gordon who Wallace described as a family friend of him and his wife, was another somewhat lengthy detailing of a man named Joseph Caleb Marsden, and then a “shopping list” of names including chess club members and other Prudential employees.

Both Gordon and Marsden had worked at the Pru where Wallace had acted as their supervisor. Both of them had been caught “cooking the books” (stealing) and thus were either fired or “left of their own accord”, and both knew each other quite well. They had also both been into the Wallace’s home while working under Wallace, with Wallace remarking that they knew where he kept the cash box (which he had always kept in the exact same spot for years). They would know – said Wallace – that the Prudential pay-in day was Wednesday, and as such they could expect the cash box to contain the most money on a Tuesday night, the very night on which Julia was murdered…

What’s more, Parry admitted to police that he knew Wallace was a regular at Cottle’s City Café – the exact same café where Wallace’s chess club met, where the noticeboard of scheduled chess matches was displayed, and where Parry’s own drama club met on Thursday evenings.

[ Note: The cash box would usually contain substantially more money than the £4 which was apparently missing, but Wallace had skipped collections that week due to illness ].

Of particular note, when the police were investigating a number of “Qualtroughs” in Liverpool they encountered an R. J. Qualtrough, who as it turned out had been a client of Joseph Caleb Marsden’s. Marsden’s alibi for the night of the murder? It is suggested by the note in a column of Wallace’s statement to police that his alibi may possibly have been that he was “in bed with flu”… Which in fairness gains some credibility because there was clearly some sort of virus going around at the time, evidenced by the fact Wallace, Julia, and Alan Close had all fallen ill around the time.

Gordon Parry’s alibi? He had spent the afternoon with a Mrs. Olivia Brine, her daugher Savonna and nephew Harold Denison (a friend of Parry’s), and another woman Phyllis Plant. Both Olivia Brine and Harold Denison attested to the fact that Parry had stayed there from about 17:30 until 8:30 PM at night. Statements from Savonna and Phyllis Plant are not in the police files and therefore they may not have given one.

But despite this seemingly bulletproof alibi, Gordon gave a completely nonsensical alibi for the night of the telephone call. He claimed that he had picked up his girlfriend Lily Lloyd from an address which he could not remember, then returned to her home spending the day and much of the night with her. This was patently untrue, and statements from both Lily Lloyd and her mother showed that Parry had arrived at their house (7 Missouri Road) in his car at about 19:35, midway through a piano lesson Lily Lloyd was giving, before briefly going off to Park or Lark Lane and returning later. Parry was in the habit of visiting his girlfriend each day it would seem, and he often finished work at 17:30. When he visited her on the night of the murder she complained that he was “late”. Although this seems inconsequential given his alibi did not rely upon her.

A forgotten testimony?: Half a decade after the murder of Julia Wallace, but before it was known that Gordon Parry’s alibi hinged on Olivia Brine rather than his girlfriend Lily Lloyd (who said she had partly falsified an alibi for Gordon), a man named John “Pukka” Parkes who had worked at the local garage recounted an incredible tale, which you can hear in his own words in the following clip…

Those who stand behind the theory that Wallace (and Wallace alone) planned and committed every step of this murder have dismissed John Parkes as either a fame-hunter, fantasist, or liar; perhaps having carried a lifelong grudge against Gordon due to envy over Gordon’s ladies’ man “Jack the Lad” persona, or bitterness at Gordon’s petty thieving from the pockets of the Atkinsons whose garage Parkes worked at (and was by all accounts very close to).

To some, the idea of Gordon volunteering information about where he had hidden a murder weapon is hard to believe.

—

But the question remains… If Wallace is an innocent man whose suspicions about Parry/Marsden/Young were correct, how could these men have expected Wallace to have received and fallen for that bogus message? How could they have committed the act without a single neighbour hearing their arrival or any chatter in the home (apparently) despite the thin walls? Was it really worth attempting to lure Wallace out with a shakey ruse for one extra day of collection money when they had the perfect opportunity to strike while he was at the chess club?

Furthermore – if as per one suggestion – a stranger to Julia went to the house pretending to be “Qualtrough”, why did he kill her instead of simply running away? Why did he return to the parlour at all? If Julia discovered him in the act why did she make no sound? Would it not just be easier to break into the home at night? Would it not be a more reliable plan to simply send Wallace on his trip using a more “normal” name and real address? Even a real address at Menlove Gardens West would allow them plenty of time to carry out such a simple robbery. Did they fear he would look up details in a directory? One can only speculate.

Antony M. Brown, in my view rather ludicrously claims she was chased down (too frightened to make noise), and put on the mackintosh before Qualtrough physically grabbed her, pulled her into the parlour and for no known reason shoved her down onto the armchair (this is the wrong chair, by the way). Apparently she simply sat there not even putting up her arms to defend herself as he grabbed the bar and smashed her across the head. Considering Julia screamed when drunken neighbour Mr. Cadwallader entered their property, the idea she would simply silently allow herself to be thrown around (without disturbing any furniture of course, or misplacing the violin case upon the armchair she was thrown onto) without so much as a peep is a difficult sell.

I do not believe this is plausible. I do think it makes more sense two people were in the home, but even so, if a noise in the kitchen by the bookcase was loud enough for Julia to hear it, it begs the question, why didn’t the Johnstons who were actually closer to where the source of this sound would have been?

On the other hand, if this was the work of William, would he be so stupid as to lie about the tram he took without knowing the telephone box was traced? Would he really use a box and board a tram in an area where he was quite well known by sight? Would he not fear the tickt inspectors and conductors on the tram would come forward to tell the police he had got on at the wrong stop?

If he planned to kill his wife would he really have stopped off for a cup of tea for a client knowing full well the milk boy/girl could call at 18:00, arriving home after this time (18:05) just to enjoy a cuppa? If he did not care about the milk timestamp would he not set a later time to ensure he actually had time to kill his wife, knowing full well by now (the milk was delivered every single evening for two years) the times between which the milk could arrive?

These are questions which have haunted the minds of many true crime enthusiasts, including famous detective novelists Dorothy L. Sayers, P.D. James, and even true-crime celebrity Agatha Christie who referenced this most baffling case in one of her novels. Seemingly Christie was in favour of Wallace, as she had her character state that the demeanour of a suspect should not be used to imply innocence of guilt.

—

Raymond Chandler called the Wallace case “unbeatable”, stating that it will “always be unbeatable.” I think he’s wrong.